The plant responsible turning sea water into drinking water is topping up island supplies for the first time in a decade and could cost £0.5m to run this summer.

The cost will ultimately have to be covered by customers - however, Jersey Water say it has been factored into existing budgets, which were being reviewed as part of its annual cycle.

It added that any tariff rises – which will come into effect on 1 January – will be published this autumn as normal.

Although the plant has been run in the last ten years, it was last used for water resource purposes in 2011.

The La Moye facility started running on 1 August and will probably run until the end of September, depending on the amount of rainfall between now and then.

It has been switched on in response to the long dry spell, which has seen reservoir capacity fall to 68%.

This week, Jersey Water – which owns and runs the plant – also announced that it would be introducing a domestic hosepipe ban from Friday in order to reduce consumption and encourage islanders to save water.

The ban could last four months, depending on the weather.

Pictured: Where the plant's waste water is released. The granite tower was used to winch blocks from the old quarry down to awaiting ships.

Costing around £8,000 a day to run, a 60-day run of the desalination plant could cost up to £480,000.

Jersey Water CEO Helier Smith said that it was budgeted but all costs had to be funded by the company’s customers.

Jersey’s desalination plant is based around a former granite quarry at La Rosière, halfway between the prison and Corbière.

The remnants of the quarry surround the centre, including the large granite structure behind the quarry pool, which can be seen from the main road, and the smaller squat block by the outfall pipes.

These structures supported cables that were used to winch quarried stone down to barges below. It’s been reported that stone from La Rosière was used to build the Embankment on the Thames.

Sea water is pumped into pipes about 150m out from the shore.

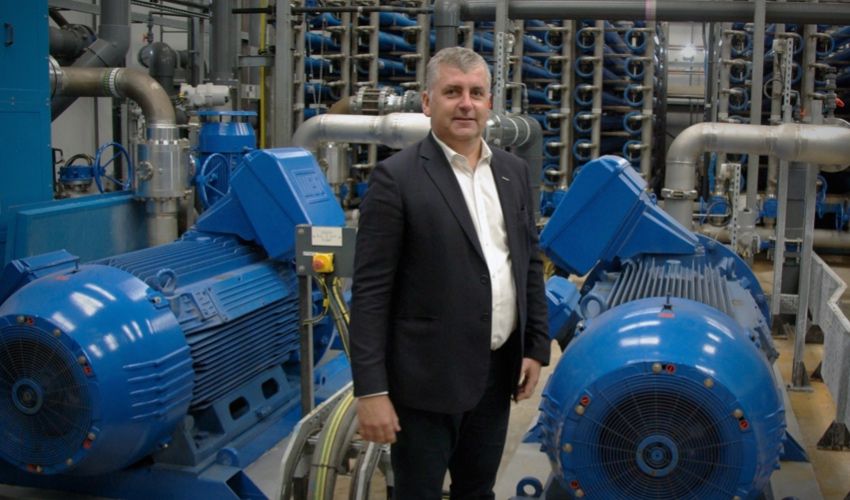

Pictured: Jersey Water CEO Helier Smith at the quarry pool, which holds seawater before it goes through the desalination process.

The pumps for seawater extraction are housed in the granite pumphouse at the bottom of small railway tracks, which are known to anyone who has walked that section of the coast.

These steep tracks are still used to transport the pumps and equipment to and from the pumphouse using a pulley system.

24m litres a day are pumped through the pipes into the deep quarry pool, where the sea water is stored.

The plant produces 10.8m litres a day of treated water and 13.2m litres of highly concentrated saline water is released back to the sea.

Before 1990, when the plant used a ‘flash distillation’ process, hot water would be released which, in the days before hot tubs, would prompt hundreds of islanders to make rockpools to relax in the salty outflow.

After 1990, when the plant underwent a significant upgrade, the process has been ‘reverse osmosis’, which is a chemical filtration process that involves no heating, thus ending the bathing pastime forever.

Mr Smith said: “As you might imagine, the distillation process was dirty, dangerous and expensive, involving the burning of significant quantities of heavy oil. After use, the plant had to be thoroughly decoked.

“Now the process, which is powered by electricity, is far cleaner and more efficient.”

Pictured: The plant underwent a significant upgrade in 1990. It can be monitored remotely from the Handois control centre but someone is usually on site every day when it is working.

From the quarry pool, water is pumped through various filters which remove sand and other particulates before the actual reverse osmosis process, when the water is pumped at high pressure through membranes which operate at the molecular level.

The output is desalinated water, which is then pumped to Val de la Mare, where it is blended with normal water to raise its mineral content.

The plant runs on electricity and uses the same amount per day as it would to power 4,000 homes daily.

Although La Rosière is expensive to run, Jersey Water is planning to expand its capacity by another 5m litres a day to 15.8m litres of drinkable water, which would also allow the company to use it more efficiently.

“This is in response to anticipated increases in the population as well as the drier conditions expected as a result of global warming,” said Mr Smith.

“When it comes to the plant itself, the challenge is the water’s mineral content so we may have to build another component to the plant to reintroduce minerals, as well as add a third or maybe fourth reverse osmosis plant.”

Last year, the company – of which around three-quarters is owned by taxpayers - published a 25-year plan to ensure the island continued to have enough water.

It concluded that a new reservoir would have to be built by 2045, or an existing one extended, if the island is going to have enough water to meet increasing demand.

CLICK TO ENLARGE: An illustration of the processes involved at the desalination plant.

Options to meet the anticipated shortfall include building a reservoir at Le Mourier Valley in St. Mary, or at St. Catherine’s or raising the height of the Val de la Mare dam.

The expected cost of delivering the first phase of Jersey Water’s plan until 2025 is around £12.5m of capital investment, with operational costs increasing by about £400,000 a year.

The company said that funding the first phase would increase the average customer bill by £22 a year, including inflation.

Other viable options include:

Jersey Water said last year that its preferred option was to use Le Gigoulande quarry in St Peter’s Valley as a reservoir, once the operator reaches the end of ‘winnable reserves’.

However, the current Island Plan earmarks the site for inert waste disposal. A proposal to safeguard a nearby field for mineral extraction, allowing the quarry to expand into it once existing reserves are depleted in seven years’ time, was rejected by States Members during the plan's debate.

Pictured: The desalination plant is based at an old granite quarry between Le Moye and Corbière.

When it comes to water, the Island Plan’s ‘Policy UI3’ states: “Development will only be supported where adequate public water supply can and will be made available prior to the first use and occupation of the development.”

The plan also states that buildings of more than five dwellings and/or more than 200 sqm of floorspace must also include grey and/or storm water recycling in their design.

“New development should incorporate all practicable water conservation and management measures to reduce water consumption and help conserve the island’s water resources,” it adds.

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.