Jersey was not a bystander in the transatlantic slave trade – but played an “active” and even “pioneering” role in it, according to a new report aiming to give a "fuller picture" of the island's history.

Published by Jersey Heritage yesterday, the ‘Report on Legacies of Transatlantic Slavery in Jersey’ sets out a comprehensive list of islanders and businesses involved in the trade in a first step towards providing a wider account of Jersey's history that is not "selective" or "biased."

The report was compiled by Jersey Heritage’s Director of Curation and Experience, Louise Downie, with research contributions from Martin Toft and Doug Ford.

One of the most striking conclusions is that one of Jersey Heritage’s key sites, which forms part of its museum - No. 9 Pier Road - was built from wealth earned through the trade.

The building was put together by Phillipe Winter Nicolle in 1818, using funds inherited from his uncle, Josué (Joshua) Mauger, who was a merchant trading in enslaved people.

However, this is only a small part of a much broader picture painted by the document, which casts its eye over Jersey’s wider culture and industries.

In this article, Express explores some of those findings, and what it means for how the island views its heritage going forward…

A name listed near the beginning of the report - under the category of people who generated wealth from trading enslaved people - is one that may be familiar to islanders: founder of New Jersey, Sir George Carteret.

Pictured: Last year, a statue of Sir George Carteret was covered in red paint and paper chains.

He was a founder of the Company of Royal Adventurers into Africa, which traded in enslaved people, ivory and gold, and his son also profited from the trade.

Carteret became a figure of much contention last year, after campaigners called for his statue to be taken down because of his involvement in the slave trade - in one incident, red paint and paper chains representing 'blood and chains' were thrown over the statue.

However, it's not only well-known names included in this section of the report - other stories are also told, such as that of Captain François Messervy and his brother, Jean Messervy.

Aboard the Ferrers of London in 1772, the pair bought and transported over 3,000 enslaved people.

During this voyage, the enslaved people mutinied three times because of the lack of food, resulting in the deaths of 43 of them and eight crew, including Captain Messervy and his brother Jean.

Others also mentioned were Richard Richardson of St. Martin, who owned or ran a sugar plantation in Jamaica in the 1660s and 1670s, and John Frederick Gibaut, one of the largest plantation owners in Salvador in the 1840s and 50s who used enslaved people.

Gibaut’s tobacco and medicinal plants plantation later went bankrupt around the same time slavery ended in Brazil in 1888.

The report notes that Jersey’s links with the slave trade “chiefly” stem from the mahogany industry, which is mentioned several times in the report.

It notes that mahogany “was harvested using enslaved people. Many Jersey merchants either owned or traded in mahogany” and that some Jersey families even "had mahogany plantations in British Honduras (now Honduras and Belize).”

Pictured: Jade Ecobichon-Gray explained that Jersey's involvement in the slave trade was primarily centred around the mahogany trade.

Aaron de St Croix and brothers, James and Clement Henry and Co, George Mauger, Francis Valpy, Francis Alexandre Bradley and George Le Geyt were identified as being part of the mahogany industry.

John and James Poingdestre were London merchants dealing in mahogany and captains of ships transporting mahogany.

Speaking on the topic in more detail on this week's Bailiwick Podcast, Jersey Heritage Diversity Group representative Jade Ecobichon-Gray, said that Jersey's involvement in trading mahogany made its relationship to slavery "fundamentally different" to what was happening in the UK.

“We know that Jersey in a lot of ways almost created its own trade route based around mahogany, and actually there were some Jersey individuals that were in some senses pioneering and actually going out to Honduras and Belize and setting up those plantations from the offset," she explained.

“So actually that’s a very important narrative and it’s a very profound narrative because we’ve never really talked about Jersey not only being part of the trade, but in some senses and some parts of the world, starting it.”

With this trade connection, some of the most common Jersey structures to end up involved with the slave trade were boats.

One boat mentioned in the report is the Speedwell, commandeered by Sir George Carteret’s son, James Carteret (who also owned a plantation in California).

Pictured: A conclusion the report reached was that Jersey Heritage's "main place of connection [to the slave trade] is Number 9 Pier Road."

The Speedwell left London 1663, and picked up 302 enslaved people at Offra, Benin. By March 1664 it had sold 155 men, 105 women and 22 boys to plantations in Barbados and St Kitts.

Another ship was the Defiance, owned by Peter (Pierre) and Thomas Mallet of Jersey and Parry.

The Defiance sailed under Captain John Kimber, a man who earlier had been tried and acquitted by William Wilberforce having been accused of causing the death of an enslaved girl by inflicting injuries because she refused to dance naked.

In 1797 it sailed from the Gold Coast with 409 enslaved people and arrived in Barbados with 408.

The records of Jersey ships associated with the trade even stretched beyond the point where slavery was abolished, with the Newport, owned by F Le Sueur, P Le Sueur and J F Le Sueur and captained by Charles Philippe Hocquard of Rozel, who was later described by his great grandson as “the last of the Jersey slavers".

The ship was stopped in 1854 by the Royal Navy, and arrested the crew for involvement in supplying materials for the transatlantic slave trade - this crew comprised of TF de la Mare, Mathew Gallichan and Charles Gallien, John Le Rossignol and Thomas Gallichan, Daniel Hacquoil and an African boy, Joseph.

In this case, the report adds that “further research [is] now being carried out to establish how involved the captain and his crew were or whether they were scapegoats."

The report notes how there was a "triangle trade" of cod and mahogany with links to South America, Newfoundland and Gaspé.

Charles Robin, a merchant and entrepreneur in the Newfoundland cod trade, and founder of a commercial empire in the Gaspé Peninsula in Canada, was part of the "triangle". His vessel, the Telegraph, was recorded as having carried enslaved people.

George Ingouville was also recorded as owning an ex-slave carrying vessel, 'Clara'.

The report explains that the slave voyages database was consulted to check if any ships mentioned in the Maritime Museum were included, but none were. However, the report acknowledged that a "deeper level of research" was now required to check their ownership and captaincy.

The Maritime Museum was, however, found to hold objects associated with slavery:

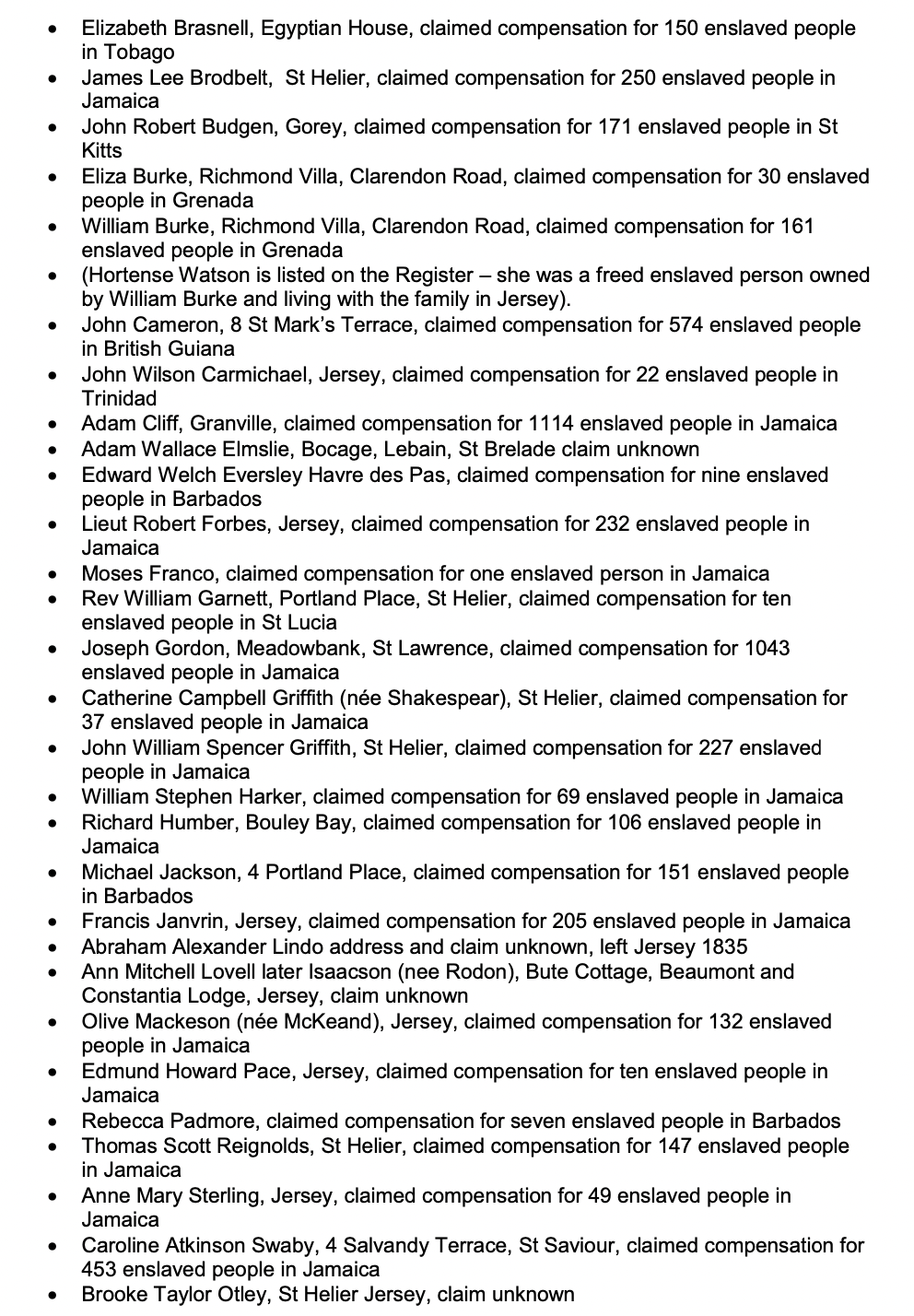

Another key element of the report was a collection of names who claimed compensation in 1834 when slavery was abolished.

The list shows that more than 30 people in Jersey were on the list, claiming compensation for enslaved people often numbering in the hundreds, and some even going over a thousand.

Pictured: A selection of Jersey names from the 1834 register.

Indeed, one claimant, Adam Cliff took compensation for as many as 1,114 enslaved people in Jamaica.

Another, Joseph Gordon of Meadowbank St. Lawrence, claimed compensation for 1,043 enslaved people in Jamaica.

The report has also recorded those with connections to the island on the list - this includes Jersey-born Joshua Gabourel, of whom Mr Pickstock was an associate.

Mr Gabourel owned a mahogany plantation in British Hondouras in the late 18th century, with his Jersey-born wife Elizabeth who lived with him in his townhouse - Hondouras later had a second wife with his mixed race wife Catherine White, who lived with him on his plantation.

The report notes that fact Joshua and Catherine’s three mixed-race children inherited their enslaved people was “an example of the complexities of history.”

A particularly notable part of the 1834 register that the report highlights is the name of Hortense Watson, a freed enslaved person owned by William Burke and living with the family in Jersey.

Ms Ecobichon-Gray said Heritage's Diversity Group want to see more stories of enslaved people living in Jersey come to light.

Pictured: Jade Ecobichon-Gray will be guest curating an exhibition focusing on Jersey's slave trade to the No. 9 Pier Road section of Jersey Museum next year.

“I think wherever possible Jersey Heritage and the Diversity and Inclusion Committee have made a real commitment to tell as many untold stories as is possible," she said.

“The reality is that we know that coming across those histories and those narratives is incredibly difficult, just in relation to the aspect of power and privilege and the way that history is told and also the history that survives in our communities and our societies.

“So that might be more difficult than we would like it to be, but absolutely wherever possible we want to bring the personal nature of this history to bear.

“We want to tell the stories of people that like Hortense Watson were enslaved and were subsequently freed, because that adds to the notion of the story and it brings about a wider conversation about [the fact that] this is not something that happened in a far flung place away from Jersey that had no ramifications for island.

“We had enslaved people on this island, and that brings the transatlantic slave trade right onto our doorstep and that requires a very uncomfortable but very necessary conversation.”

On future steps, the report states that Heritage now has enough knowledge to start creating projects addressing the issues raised.

This includes further audits and research in areas, including: people who opposed the abolition of slavery; people who opposed the rights of other disadvantaged groups, expressed discriminatory views or carried out discriminatory activities; collections of human remains or items of religious or cultural significance from outside of Jersey; people or companies which promote the cause of equality, diversity and inclusivity either now or historically.

Jersey Heritage will also be working with academics from Liverpool to create a guide for appropriate and sensitive terminology to use in future.

Pictured: A number of initiatives, including a new plan for Heritage's blue plaque scheme, are now underway following the report.

Heritage’s blue plaque scheme will also be reconsidered to "include previously excluded voices".

One plaque acknowledging where former Lieutenant-Governor Sir Tomkyns Hilgrove Turner (1764-1843) lived, for example, does not include that he claimed compensation for 485 enslaved people in Jamaica when slavery was abolished. Consideration may be given to including such information.

The Diversity Group also wants Jersey Heritage to support the island community in marking International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade on 23 August 2022.

At the centre of these initiatives will be an exhibition opened that day, guest-curated by Jade Ecobichon-Gray, which will be based in the dining room of No. 9 Pier Road - which includes mahogany furniture, stairs and rails - and give information on the Jersey’s links with transatlantic slavery, with particular focus on the mahogany trade.

It will also include information on how white islanders can be good allies to Black and mixed race people.

Speaking about what she hopes the island will begin to take out of this movement, Ms. Ecobichon-Gray emphasised she did not want it to be about feeling guilt, but about moving forward with a better understanding of our history.

“I think it would be fair to say that all of us acknowledge that this is not about cancel culture,” she said.

“It’s not about taking information away, if anything it’s about adding information - we want to be able to open up history and tell the nuanced and complex story that sits there.

“And so if things haven’t been mentioned that feel necessary for an understanding of who individuals were, I think that’s absolutely a conversation to be had

"This is not about taking things down, it’s about adding to the story and making sure that people get the whole history, not just a part of the history that feels more comfortable.”

Express sat down with Jade Ecobichon-Gray to talk about Jersey's links with slavery in further depth...

Follow Bailiwick Podcasts on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Deezer or Whooshkaa.

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.