The V sign is now a symbol synonymous with liberation, with freedom and with solidarity.

But during the Occupation, it was also a powerful weapon against the enemy, a way to assert that the Island was far from beaten yet.

In this piece, Express' occupation expert, Colin Isherwood, traces the origins of the 'V' sign, as well as the German effort to claim it for themselves...

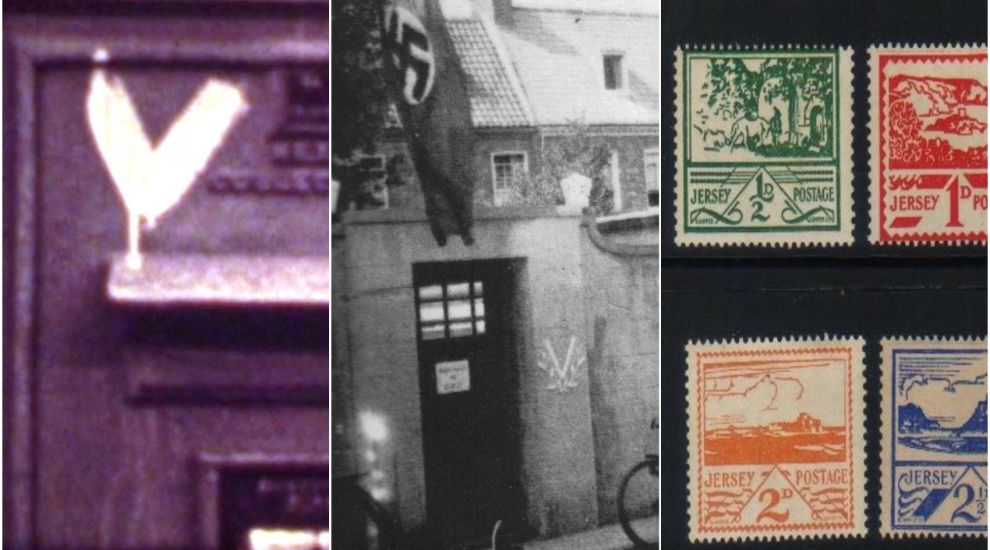

Pictured: ‘British Victory is certain’ with a ‘V’ sign daubed on a German road sign at the bottom of Queens Road.

80 years ago this month, the former Belgian Minister of Justice, Victor de Laveleye, began giving BBC radio broadcasts in which he encouraged people in German-occupied countries to use a ‘V’ for Victory as a rallying emblem. Within weeks of the broadcast, hundreds of ‘V’ signs began to appear across Europe.

Surprised by the success, the BBC set out a 'V for Victory' campaign which was headed by their Assistant News Editor, Douglas Ritchie who posed as Colonel Britton.

His broadcast always closed with the first few notes from Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, the Morse code signal for the letter ‘V’, three dots and a dash. The irony being, Beethoven was German.

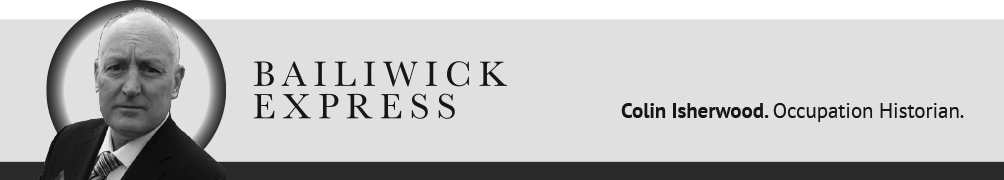

Pictured: A German notice warning against ‘V’ signs.

The campaign was seen as morale-boosting and a subtle form of sabotage for those civilians in Occupied Europe. It was also endorsed by British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill who was often photographed giving a ‘V’ hand sign.

News of the campaign soon reached the Channel Islands and islanders began taking part in this act of defiance against the Germans.

Numerous ‘V’ signs were daubed on walls and buildings, much to the annoyance of the Germans. One such incident occurred during the night of the Saturday 28th June 1941, when ‘V’ signs had been painted in and around the Rouge Bouillon area of St. Helier.

Pictured: V signs daubed on a Jersey letterbox. Pictured at Liberation.

The perpetrators had painted ‘V’ signs on walls, houses and even chalked a ‘V’ on the road. But what really annoyed the Germans was the defacing of one of their signs.

The German authorities were furious and immediately issued three warnings if the perpetrators did not hand themselves in.

On 10th July 1941, people living in the Rouge Bouillon area did indeed have their wireless sets confiscated as a form of punishment, and the Germans selected several male civilians to stand guard all night at the bottom of Queen's Road.

Pictured: The Mayfair Hotel, St. Saviour’s Road, with a ‘German ‘V’ sign at the entrance.

After a few days, the confiscated radios were returned to their owners as those responsible had been apprehended. They were two young girls who pleaded guilty, and were subsequently sentenced to nine months imprisonment, which they had to serve in France. Fortunately, once their sentence had been served, they both returned to the island safely.

This incident did not deter many islanders, who continued with the campaign of defiance - and, if anything, it gained in strength.

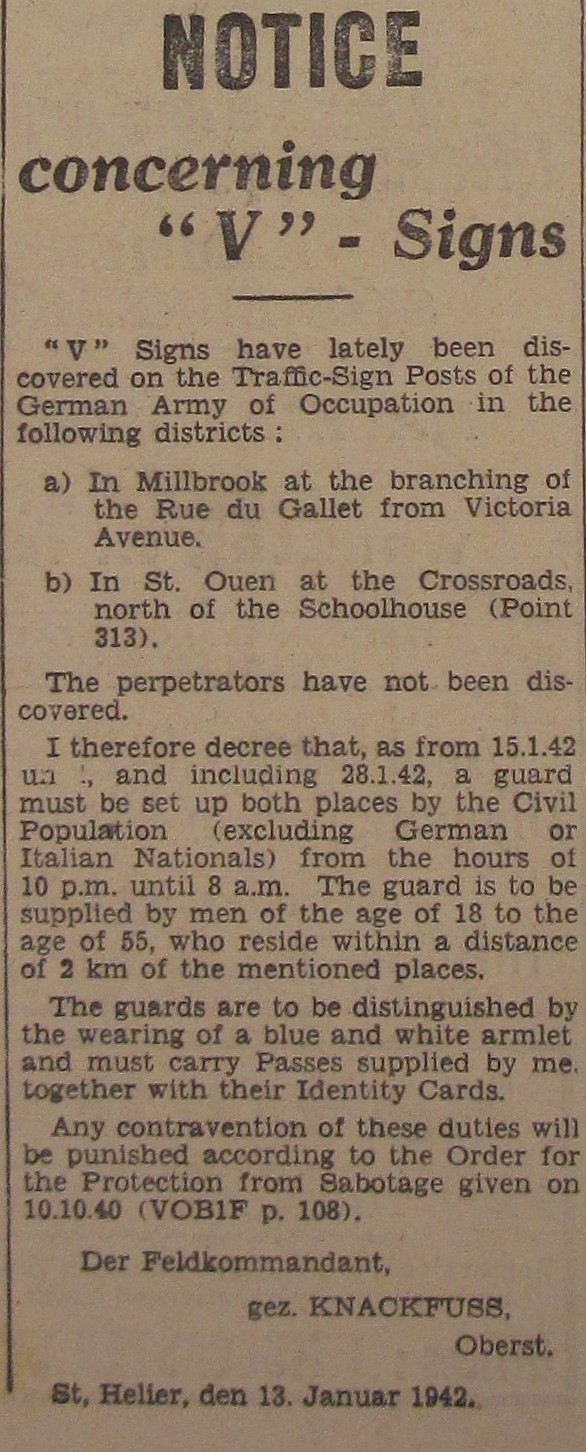

The symbol was engraved in cups, stitched in clothes, embroidery and when local artist Edmund Blampied was commissioned to design a range of Jersey stamps and bank notes, he cleverly hid ‘V’ signs within the artwork.

Although the campaign in Jersey did no harm to the Germans, it did infuriate them immensely and rewards of £25 - over £1,000 in today’s money - were offered for any information leading to the arrest of any perpetrator.

Pictured: The faint remains of a ‘V’ sign at Robin Hood, St. Helier.

Rather than continually try and remove the signs, which they sometimes struggled to do, the German’s began to adapt the sign as their own ‘Victory’ or 'Viktoria’ sign with the addition of laurel leaves under the ‘V’.

It is alleged that the idea came from a Guernsey Reverend, who told the German authorities: “If you don’t like people putting up ‘V’ signs, why not put some up yourself!”

Whether the idea originated in Guernsey is unclear, but Occupation diarist Leslie Sinel noted on 21st July 1941: “The Germans commence putting up the ‘V’ sign themselves, occupied buildings and motor vehicles receiving most attention.”

Pictured: Edmund Blampied stamps showing the ‘V’ sign.

Knowing that the Germans had their own sign did deter many islanders as it no longer offended in the same way, but the campaign continued.

In the end, many people felt the ‘V’ stood for more than just Victory - it was a symbol for solidarity, resistance and never giving up.

Today, the V sign is still used to celebrate all types of events.

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.