A Dunelm employee, who hurt her shoulder while lifting heavy items at work, will be able to continue her fight for discrimination compensation after her employer failed to argue she shouldn't be considered ‘disabled’.

Anna Genda brought three separate claims for disability discrimination to the Employment and Discrimination Tribunal - two relating to 2019 and one in 2020.

But, before Ms Genda's case could be heard, Dunelm applied to have it thrown out on the basis that she wasn't 'disabled'.

The Tribunal's Deputy Chair, Advocate Ian Jones, was therefore left to decide whether she was according to the Discrimination Law.

In a hearing last month, he heard that Ms Genda had injured her left 'labrum' – a piece of cartilage which is part of the internal stabilising structure of the shoulder - whilst lifting “heavy products” at work in April 2019.

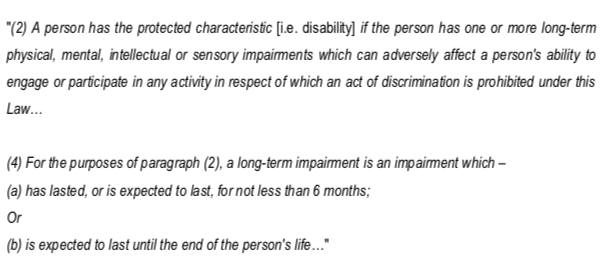

Pictured: Paragraph 8 of the Discrimination Law was the focus of much of the case.

She sought medical care the day after the incident and Dr Patrick Armstrong, a Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, said surgery would be needed to repair the damage and alleviate her symptoms.

As a result of her injury, Ms Genda couldn’t open the shop in the morning because she could not move or lift the doors on her own or carry out tasks involving lifting or moving heavy objects.

Following a risk assessment, Dunelm accepted it would be necessary to change her working hours, activities and department.

However, Advocate Jones noted in his judgment Ms Genda hadn’t been forced to take time off work because of the injury to her shoulder.

“To her credit and that of [Dunelm], both parties sought to manage the condition with the result that the Claimant did not have to take any period/significant period of sickness absence.”

Pictured: Advocate Ian Jones, the Deputy Chairman of the Employment Tribunal, heard the case.

While Dunelm, represented at the hearing by Alastair Hodge, accepted Ms Genda had an ongoing physical impairment at the time, they suggested this did not fit the definition of disability in the Discrimination Law.

They also argued she had failed to show she had been adversely impacted by her injury whilst at work.

“I was asked to draw the inference that there was no adverse effect on the basis that no sickness absence had in fact been necessary,” Advocate Jones wrote in his judgment.

Ms Genda argued to the contrary, saying the injury had a “negative effect on her ability to do normal daily activities”.

The Deputy Chairman eventually rejected Dunelm’s argument, saying the law did not require someone to prove they had in fact been adversely affected but rather that their injury “might or has the potential to have an adverse effect” on their ability to "engage or participate in any activity".

“It seemed to me that an employee who continues to work in spite of an injury and does not seek to take time off as a result is precisely the sort of employee that any employer would prefer to have in its employ,” he added. “Provided of course that matters are managed in a way so as not to exacerbate the injury of the employee or place anybody else in harm's way.”

Pictured: The Employment Tribunal had to determine whether Ms Genda was 'disabled' according to the Discrimination law before hearing her claims.

Dunelm’s and Ms Genda’s interpretations of the law were opposite with the former opting for a narrow view while the latter was “incredibly wide”, according to Advocate Jones. Ms Genda argued that once a physical impairment had been demonstrated or conceded, one was likely to be 'disabled' as a matter of Jersey Law.

“The Claimant was asking me to interpret 'any activity' as meaning just that and not to be interpreted in any restrictive way; the Claimant contended for the widest possible interpretation of the Law making it as easy as possible for someone to fall within the definition of disability,” Advocate Jones commented.

However, he eventually concluded that Ms Genda was disabled as a matter of law, adding that her physical impairment “plainly did have the potential” to cause an adverse effect in the workplace.

“Her work required physical work to be done, be that lifting or moving heavy objects; it is difficult to see how any to an arm or shoulder, particularly one that required surgical attention would not have the potential to have an adverse effect,” he wrote.

Pictured: Advocate Jones said short-sightedness could be considered a disability.

Advocate Jones also explained that, under the law, he himself could be considered 'disabled' due to his long-term short-sightedness, which might prevent him from reading something on a screen.

“Plainly my poor eye-sight might adversely affect my ability to do my job,” he explained. "As a matter of Jersey law and by reference to the Law that is all that I need to demonstrate in order to meet the definition of disabled.”

He went on to say the law does not intend to make it difficult for people to claim they have been discriminated against on the grounds of disability. Instead, he said, the purpose of the Law is to protect “as many as people as possible from being discriminated against in as comprehensive way as possible”.

“In our 21st century society whether or not someone is in fact disabled is entirely irrelevant, or at least it should be,” he added. “The important question for the Tribunal, and I would say our society in general, is whether or not someone has been discriminated against because of their disability."

Ms Genda’s disability discrimination claims will be heard at a later hearing.

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.