Large white crosses are being painted in public places across Jersey in an act of surrender after attacking German forces dropped an ultimatum to island authorities by plane.

That was the situation 80 years ago today, following a nervous build-up that saw islanders rush to the banks in their droves and even, sadly, put down pets as they awaited an invasion.

In his latest column for Express, Occupation historian Colin Isherwood explores life in Jersey in the weeks before Occupation, and the preparations and execution of Operation Green Arrow (Grüne Pfeil), the code-name given to Germany's plans to invade the Channel Islands...

"On 10 May 1940, Hitler launched an invasion of Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg and France.

The ‘Phoney War’ was over, but, whilst this Blitzkrieg or (Lightening War), as it was called, was taking place in Europe, Jersey was getting ready for its holiday season with three weekly sailings from Southampton and a regular flight service with Channel Islands Airways, and so there seemed no immediate concern.

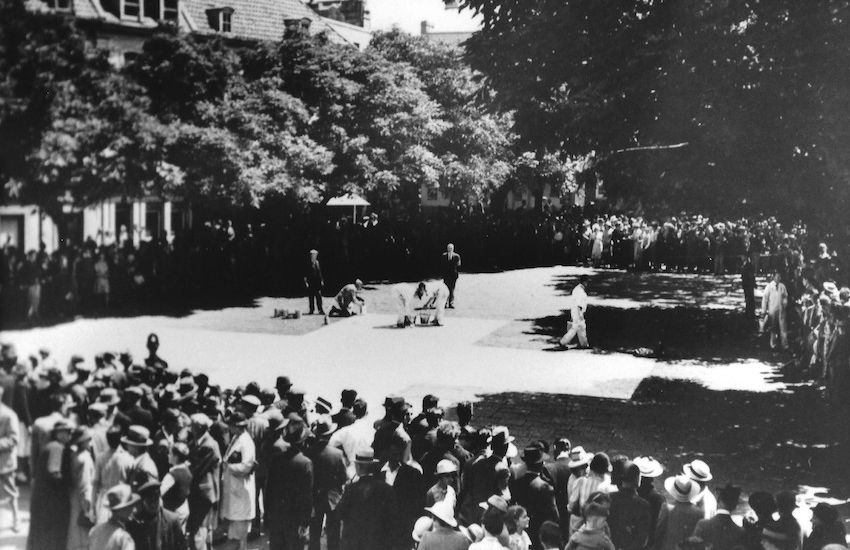

Pictured: The Bailiff addresses anxious islanders in the Royal Square on Thursday 20 June 1940.

After a sitting in the States Chamber, Jersey’s Bailiff, Alexander Coutanche, listened to the news on the radio, announcing the Germans had just crossed the Seine at Quillebeuf, which is quite close to the Channel Islands.

Startled by this news, Coutanche immediately contacted the Home Office and, after a brief call, realised the possibility of an invasion.

Whitehall understood the difficulty in defending the Channel Islands strategically and, after days of deliberation between the Home Office and War Department, the answer finally came in the form of two telegrams.

The first read: “War Cabinet decision is that the island of Jersey is to be demilitarised."

The second message read: “The Channel Islands will not - repeat - not be defended."

Shortly after receiving the news, the Bailiff addressed a large crowd in the Royal Square where he read the message out. He told them to remain calm and stay in the island. For those wishing to leave, transport ships would be available to take people to England.

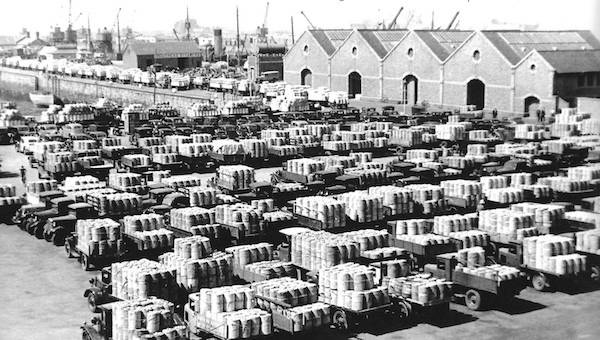

Pictured: Lorries loaded with potatoes waiting to be exported to England.

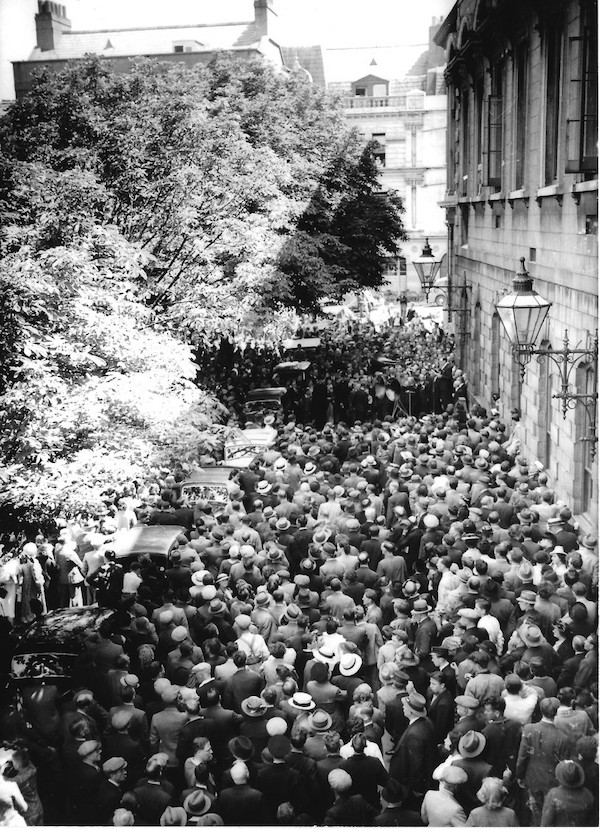

After the Bailiff’s speech there was panic - people didn’t know what to do for the best. Over 23,000 islanders immediately registered at the Town Hall to leave, but many changed their minds, not wanting to leave their homes.

Less than 10,000 actually left, most of whom were men of fighting age wanting to join the British armed forces. Those that left had a long journey to Southampton on old, grubby transport and cargo ships, leaving behind, friends, family and loved ones.

These events took their toll on the island in many ways - houses and shops were left empty, while the banks were so besieged by islanders intending to leave, taking their money with them, that many imposed withdrawal limits of £25 - the equivalent of £700 in today’s money.

Sadly, over 5,000 pets were put down at the Animals' Shelter. The staff had to work on a shift rota to clear the dead animals. Many of these animals were put down by owners who later changed their minds and stayed.

Pictured: The 28 June 1940 attack, painted by Gerald Palmer.

Although unaware of all this chaos in Jersey, the German invasion force in France was fully aware of the Channel Islands. A message from Berlin addressed to the German authorities in France read: “In order to protect the local sea area, it is necessary to destroy the cable communication from the British Channel Islands to England. Ask permission for motor torpedo boats and minesweepers to support this raid by the Naval Assault Group."

The second message came a short time later: “Occupation of the British Channel Islands is urgent and important. Carry out local reconnaissance and execution thereof. Written orders will follow."

This later message was serious, as it meant the planning of an invasion of the Channel Islands, which was then code named Operation Green Arrow (Grüne Pfeil).

Pictured: The Bailiff, Alexander Coutanche with German Air Force Officers at Jersey Airport on 1 July 1940.

To put such a plan in place and without large numbers of casualties, the Germans needed to know if the islands were defended. Although several aerial reconnaissance flights over the islands had been carried out, they had been at high altitude and were inconclusive.

The only material the Germans had gathered was from a German agent who travelled to Guernsey in 1938. The agent reported seeing forts and castles, but they seemed old and obsolete, so this was also inconclusive.

The only practical way for the Germans to discover if the islands were defended before launching a full-scale assault was by further reconnaissance flights.

Over the next few days, life in Jersey began to get back to some form of normality. Shops that had been closed were now open and farmers continued transporting their potatoes to St. Helier Harbour for export.

Farmers were warned not to congest the Harbour area with their lorries in case the Germans mistook them for military trucks, which is what ultimately what happened.

Islanders were still anxious, but there was a surreal calm and, if not for the frequent low-flying German aircraft, it would have felt the Germans had bypassed the islands.

Friday 28 June 1940 was a beautiful hot and sunny day in Jersey. People were busy at work and St. Helier Harbour was a hive of activity with lorry-loads of potatoes ready for export. St. Aubin’s bay was calm, with several people taking an afternoon swim.

Pictured: Shrapnel damage from the 28 June 1940 attack, still visible on the Albert Pier.

At precisely 18:45, three German Heinkel bombers swept across the east coast of the Island. The Germans needed to test the defences which they felt were present in the Island - this was no reconnaissance flight.

No alarms sounded; the attack came too fast. Machine guns and bombs hit at La Rocque, Fort Regent, South Hill, Commercial Buildings and St. Helier Harbour.

Fires blazed and hundreds of panes of glass were shattered in the attack, including the stained-glass windows in the Town Church. This is still evident today, as is the shrapnel damage on Commercial Buildings and along the Albert Pier.

In total, over 180 bombs were dropped and 11 islanders were killed, with many more injured. The raid in Guernsey was far worse, with 34 dead and nearly 100 people injured.

Just after the attack, the BBC World Service declared the Channel Islands were demilitarised. The raid on the islands was not mentioned until early the next morning.

The timing of the radio announcements made it appear that the Germans knew the islands were undefended, but still attacked.

Over the next two days, several air raid alarms were sounded in Jersey, but there were no attacks. The island was on a high state of alert; curfew and a restriction on the use of motor vehicles had been re-imposed. Most islanders felt scared and afraid of what was to come.

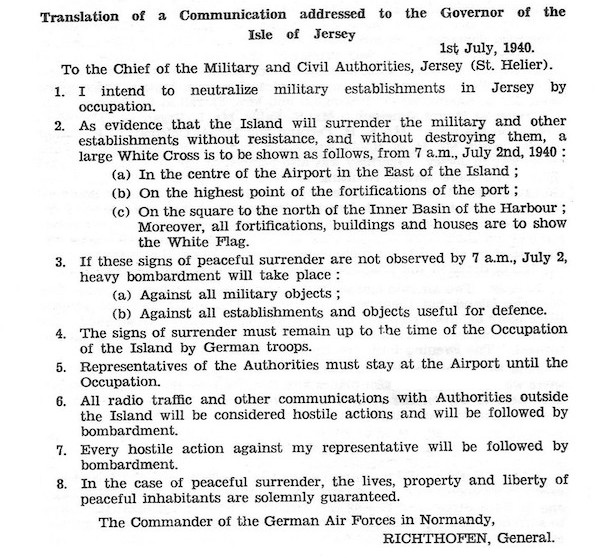

Pictured: A copy of the 1 July 1940 ultimatum of surrender signed by General Richthofen.

At 05:50 on Monday 1 July 1940, an ultimatum of surrender addressed to the island authorities was dropped by plane onto the island.

It instructed that large white crosses be painted in conspicuous open spaces and white flags be hung from public buildings and places.

This order had to be completed by early the following day and was signed by General Richthofen, Luftwaffe Commander of Normandy.

At noon the same day, a lone German aircraft flew over the island. After observing a sea of white flags and large white painted crosses, they landed at Jersey Airport.

By 15:30, the Bailiff arrived at the airport to be told by a German Officer: “You realise you are occupied,” to which Coutanche replied, “Yes.”

Five years of German Occupation had begun.

Pictured top: A large white surrender cross being painted on the Royal Square on 1 July 1940. (All photographs courtesy of Colin Isherwood)

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.