Concerned that “myths often get repeated” without challenge, it was one islander’s instinct to go against conventional wisdom that ultimately led him to identify scores of potential ‘lost’ Neolithic passage grave sites - including one now earmarked for the new hospital development.

While many associate the word ‘Hougue’ and its diminutive ‘houguette’ with the presence of prehistoric tombs - thanks to areas like La Hougue Bie - Société Jersiaise researcher Nick Aubin questioned whether this was quite right.

Delving into the word’s origins, he realised that, in fact, there was “no justification for saying a ‘hougue’ is a dolmen”, as it actually signified a hill or a mount.

“Hougue Bie was essentially called Le Hougue Bie because it was on a hill. Then I thought, ‘Hold on, if ‘hougue’ means ‘hill' and not a dolmen, we can discount the ideas of [older dolmen] distribution maps’,” he recalled.

“I then started to go back and look at all of the historical records.”

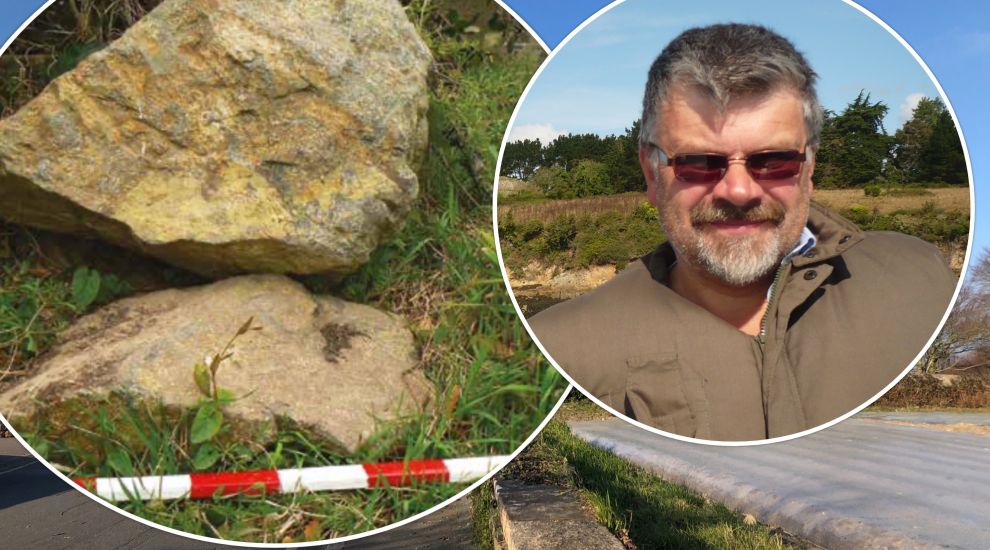

Pictured: Many people think 'hougue' means 'dolmen', when it actually indicates a hill, Mr Aubin found.

But, rather than look at more modern, detailed writings, Mr Aubin headed for the original recordings.

“What has tended to happen is that people have repeated what’s been said in the past, rather than going back to the original source documents. When you do that, you suddenly see there were a lot of sites around that have been forgotten.”

From there, he started to plot them out, realising that our understandings of the boundaries of certain areas may differ significantly to how they were recorded historically.

This, Mr Aubin said, is likely the case of a possible site at ‘the Dicq.'

“We tend to think of the Dicq as down on the beach, but actually the Dicq was an inlet that goes all the way up to Howard Davis Park. Where the Post Office was on Mont Millais – I think it was probably there, as the Dicq went up towards that.”

It was this technique of revisiting the “myths” and reconsidering boundaries that led him to uncover scores of other potential sites - most of which were around St. Helier.

Pictured: Mr Aubin went back to the source texts for his research.

“It turns out that most of the locations seem to be around town – around those [former] coastal marshes. There’s a suggestion from Guernsey, where they’ve done some isotope analysis of some of the bones, that the people were living off marine-type [food] – not necessarily fishes and things - but cattle grazing off salt marshes.

“My thought is really that if we discount all the old distribution maps, what we’ve actually got is sites clustered around town which would of couse have been a big marshy area and the east of the island, and St. Ouen.”

While many may now be covered by development, one potential Neolithic Megalithic monument site he discovered does have archeological potential - Field 1550, opposite the crematorium and bordering the nearby cemetery.

Writing in the 1930s, historian Hawkes had suggested there was evidence of two monuments: one at Le Rouge Bouillon and the other near La Mont Patibulaire or Westmount.

But, having delved into the writings of Falle (1734), Morant (1761) and Baker (1840), Mr Aubin countered this, suggesting that the records actually pointed to a single site on the eastern side of Westmount located in the field south of the cemetery.

When he decided to inspect the field himself, he was surprised by what he found.

Pictured: The rocks Mr Aubin found in Field 1550.

“I looked inside the entrance of that field, and it had this chunk of rock with little crystals on and I remembered that one of the descriptions of the site talked about the rock being a different material than the hill, so I thought, ‘This is a hugely distinctive rock, let’s see where I can find it.’ So I went down with a geologist looking at all the outcrops down on the beach below.”

It emerged that the stones were ‘porphorytic andesite’ similar to an outcrop of rock immediately to the south of the Victoria Marine Lake on West Park.

“I can’t guarantee it comes from there, but it’s the only one we found where the crystal pattern seems to match the pattern I found up on the hill,” Mr Aubin explained.

“So the thought was, we know Neolithic people didn’t have access to modern quarries, so they pulled off rock where they could get the rock – on outcrops on the edge and down on the beach.

“It seemed to be the most plausible explanation.”

From there, he drew up a report and shared it with Jersey Heritage, who believed there was a good enough case for it to be put forward to Planning for archeological protection with the hope of eventually being able to excavate.

Video: A look around Field 1550.

While there might not be visible evidence of a monument on the field site, excavation work would allow researchers to identify what are called “stone sockets”, which will ultimately help them figure out what pattern the stones forming part of any monument might have followed.

“To sit an upright stone – these stones are 6 or 7 feet tall – you have to dig a hole to put it in. So there is a hole there, and what they would do is prop them up with little stones.

“Imagine you’re trying to put an umbrella up at a beach, you’d probably dig a hole and put little stones around it in the sand on top. This is fulfilling the same function.

“If that main upright stone is pulled out and then broken up, what you’d end up with is a hollow where the stone was. So if you clean down carefully, you can find the hollow. You clean off the destruction debris, the fragments of broken stones, clean off the top soil, if you excavate carefully, you should see all these little dips, little hollows, of where the stones were fit.”

If given the chance to excavate, archeologists might also find a small level of shale beach pebbles - an indication of flooring.

Such a finding was encountered at Mont Félard in the 30s.

Years later, two large granite slabs were found on the western side of Mont Félard, around 50 yards north of the current Hotel Cristina. It was believed these were originally derived from the area of the bed of shale pebbles.

Pictured: Designs shared last week showed the Knowledge Block and a car park planned for Field 1550.

Unfortunately, however, a modern house was constructed on the site of the pebbles.

“The slabs still exist but the site itself with the archaeology is gone.

"Once you pull the stones out, they’re interesting, yes, but you lose the real archeological value – the value was of the stones in the site with all the deposits next to them.”

When it comes to Field 1550, Mr Aubin says he hopes that history doesn’t repeat itself.

Heritage Advisor to the Our Hospital Project, Steven Bee, told Express it was likely that “anything of historical interest or importance in the field is already in a fragmentary state due to repeated ploughing”, but did pledge that the planning team would take historical aspects of the site into consideration.

To this, Mr Aubin says: “It could have been ploughed up, who knows, but there’s potential.

“It’s worth the chance of at least having a watching brief and a few trial excavations in the most likely locations.

"It’s not the whole field, it’s the top part of the field, by the cemetery around here. A few trenches around there – maybe we find something maybe we don’t.

“It would be a shame to bulldoze it all and not have a good look first.”

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.