Losing your job can be a distressing time and for one Customs officer at the end of the 19th century, it marked the start of a ten-year campaign to put right what he saw as a serious injustice.

On 25 March 1882, Clement Sorel was reappointed as the Principal Impôt Officer, with Francis Le Sueur called upon to take oath as First Sub-Agent for the same period.

This seemingly innocuous act was a blow for the previous sub-agent, Henry Charles Bertram.

Until 1882, Bertram had served as Sub-Agent to the Impôt for 32 years, first being appointed to the post in March 1850. However, in 1881, the relationship between him and principal officer Sorel broke down.

That year, John Le Riche had been sworn in as one of Sorel’s subordinate and it was the duty of Bertram, Le Riche and another man by the name of Cartwright to keep the coast of Jersey free from smugglers.

From the beginning, Bertram and Le Riche’s relationship was problematic.

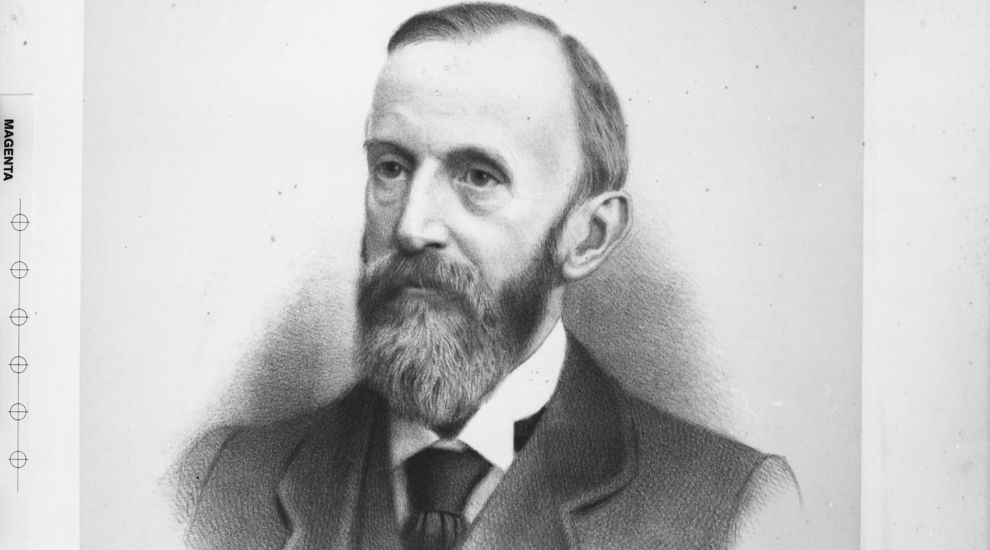

Pictured: The Bailiff, Sir George Bertram. (Société Jersiaise)

Among the paperwork at Jersey Archive relating to what happened next is a note that Bertram wrote in May 1881. In it, he remarked that Le Riche was supposed to meet him at the Town Railway Station but he didn’t turn up. Le Riche claimed he was there and that Bertram must have missed him. Bertram accused Le Riche of “having told a wilfull and deliberate lie”.

In a letter to William MacKay, Customs House Officer in Gorey, a few days later, he wrote that Le Riche had been astonished that he was expected to patrol the entirety of the Island and not just the area near his house at Havre des Pas and that he was impertinent enough to tell Bertram that if he was sent anywhere at night on his own, he wouldn’t go.

With the relationship fracturing, Le Riche handed in his resignation, which Bertram passed on to Sorel, as well as informing the Administrators of the Impôt. However, Sorel didn’t act on it and the relationship between Sorel and Bertram went downhill.

Bertram alleged that he took into custody various French smugglers caught with enough barrels of brandy for them to be prosecuted. However, Sorel’s instruction was for the items to be returned to their owners and the boats released.

Bertram claimed that the Principal Agent “was playing into the hands of the smugglers”. He also said that he did not make these accusations “behind his back, I do so openly, publicly and in writing, and I say that it was a most disgraceful proceeding”.

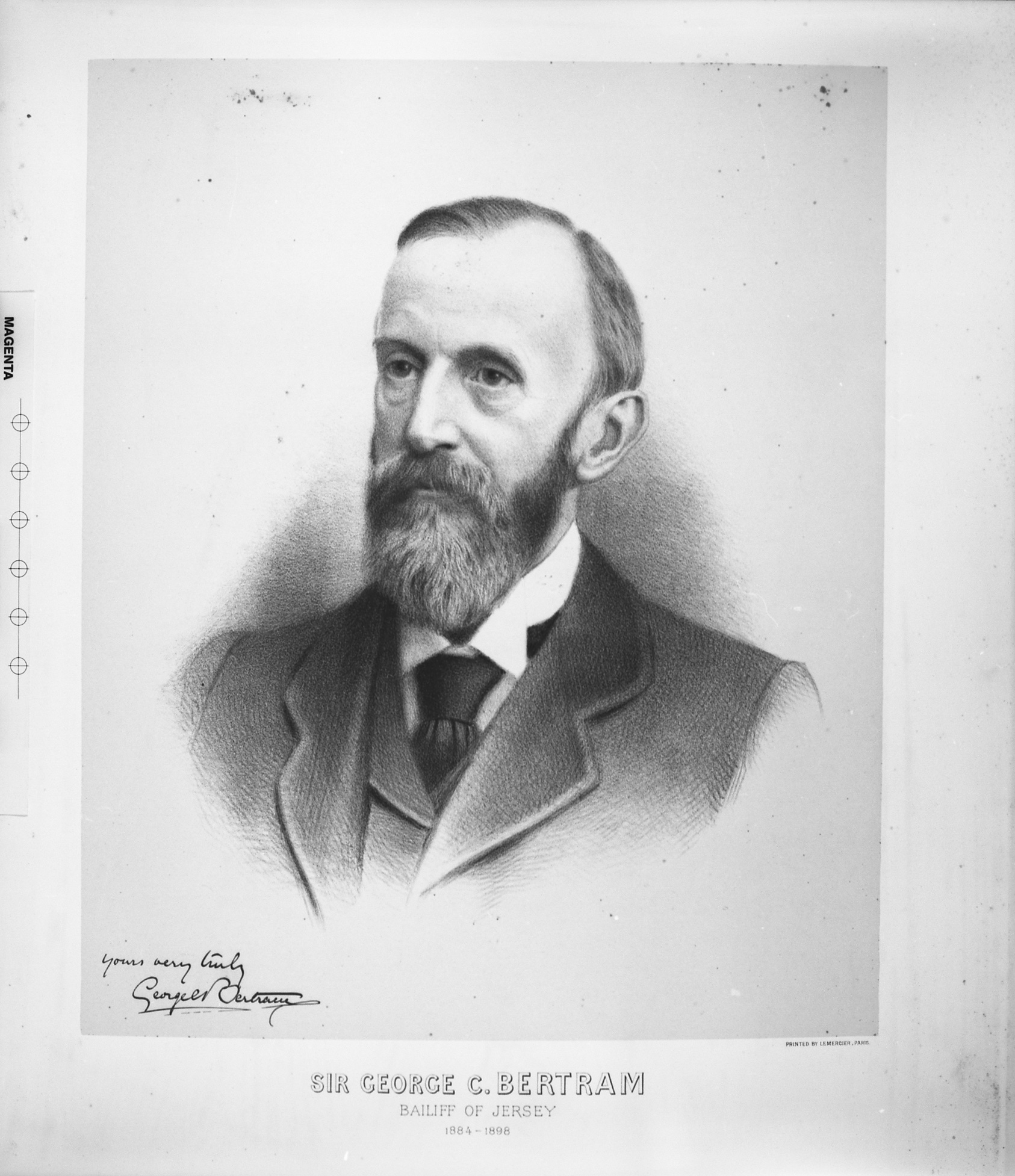

Pictured: Letter from Henry Bertram to the Lieutenant General Lothian Nicholson explaining his case in the 1880s. (Jersey Heritage)

On 22 November 1881, there was a preliminary meeting with the Administrators of the Impôt and Bertram was invited. At this secret meeting, Bertram claimed that he was accused of showing animosity towards Le Riche, which had led to his resignation. He said that on the contrary, he had treated him with kindness and respect, promising him that he would teach him all he knew, as well as paying for his dinner on his first day of work.

A further meeting was called a couple of days later on 24 November. Writing about this, Bertram said this meeting was also private and not recorded in any official records and that he continued to be accused of things. This led directly to Le Sueur being appointed to replace him in March 1882.

At Le Sueur’s swearing-in at court, Advocate Durell requested permission to speak on behalf of his client, Bertram, who was being replaced. The Bailiff denied him this opportunity, saying that Bertram’s term expired on 25 March and therefore he didn’t require notice to be replaced. However, Bertram did not go quietly into retirement.

Bertram wrote numerous letters to those in authority about the injury caused to him. He also ended up in court himself in December 1883 when he brought a case against Charles Blampied for grossly insulting him on the Écréhous. Bertram had bought a property on the Écréhous a few years earlier in order to keep an eye out for smugglers.

Bertram came into Blampied’s home for refreshments as he had run out in his house. Blampied joked that if he ran out of spirits he could ask his friend, Clement Sorel, the Principal Agent of the Impôt, to get them out of bond for him.

In response Bertram declared that Sorel was “a scoundrel, living on Government pay, and had defrauded the public for upwards of half a century”. When Blampied denied this, Bertram called him a fool and a traitor to Freemasonry. In response, Blampied called Bertram a, “d- liar and a b- fool.”

The court case garnered a great deal of interest. Newspaper reports at the time recorded that there was laughter from the watching crowd, as well as a request from Sorel to speak, which was denied by the Magistrate. At the end of the case, the two men were bound over to keep the peace between each other.

However, Bertram’s campaign continued. He wrote a satirical piece about the administration of justice, the law and the impôt in the Écréhous in 1884. In 1887, he wrote a petition to Queen Victoria asking her to intervene on his behalf.

Later that year, he published a number of circulars with allegations against the authorities. One of the main subjects of his ire was the Bailiff, Sir George Clement Bertram, who was Attorney General when the incident took place.

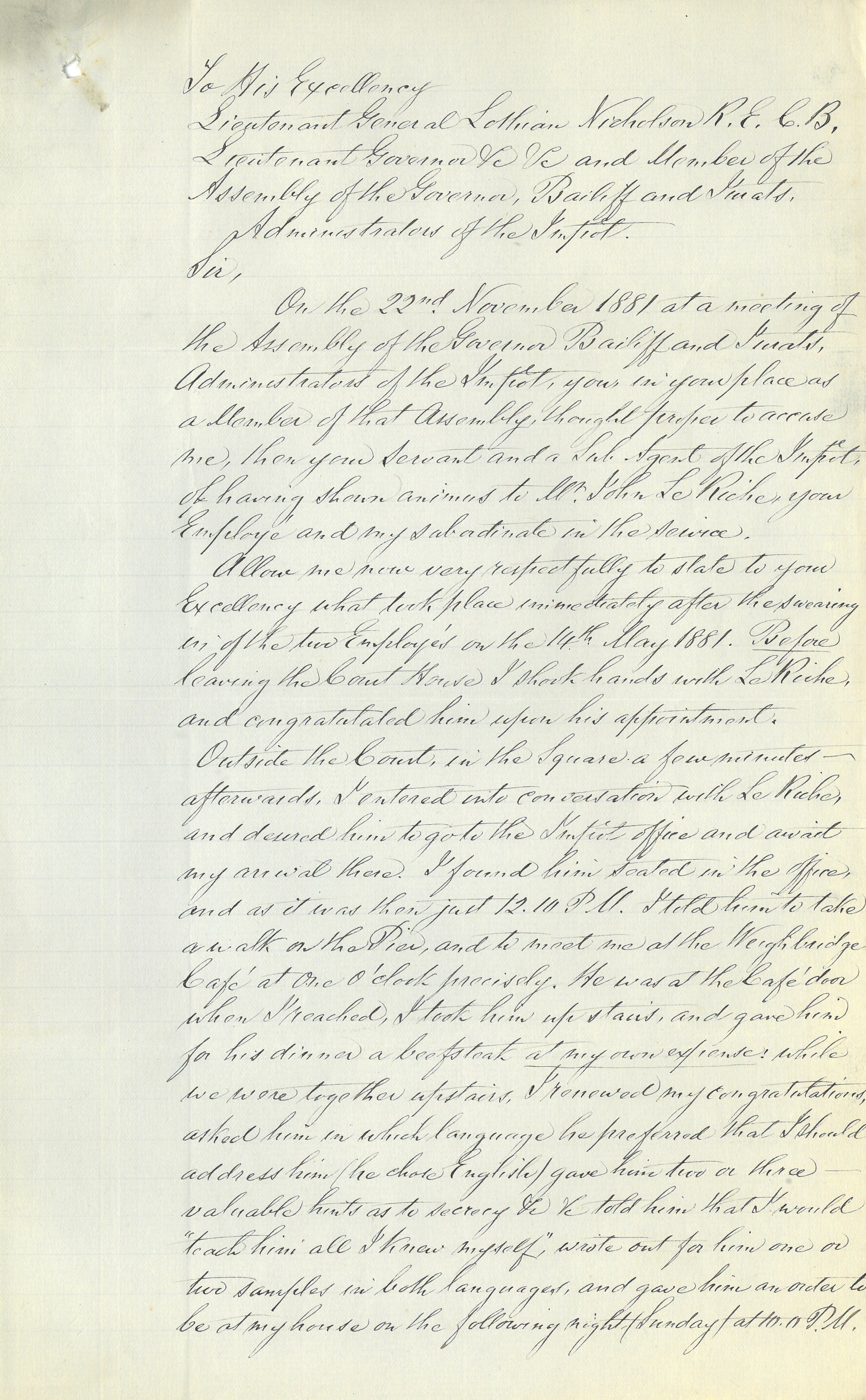

Pictured: Henry Charles Bertram's first printed circular from 10 December 1887. (Jersey Heritage)

In his second circular, he wrote: “You are a false-hearted fair-weather friend, Sir George, You are a Sneak Sir George, “Sad was the hour and luckless was the day” for me “when first” I trusted you. I little thought when you wrote for me the following lines in one of my letters to the Administrators of the Impôt, that I should ever be able to turn them against yourself, now how applicable they would be with a very slight alteration; you are “a man in whom I have no confidence whom I dare not trust.””

He told the Bailiff that he would probably succeed as “although I have right on my side, you have all the might on your side,” but that he wouldn’t back down.

Pictured: Henry Charles Bertram's second printed circular from 27 December 1887. (Jersey Heritage)

Bertram claimed in later circulars that the revenue of the Impôt had gone down since his departure as a result of smugglers being allowed to bring their wares into the island without consequence, even going as fair as to accuse Le Riche of working with the criminals.

Pictured: Henry Charles Bertram's eighth printed circular from 12 July 1888. (Jersey Heritage)

In one of his letters, he wrote that he had heard that Jurat Briard had suggested that he be brought before the Royal Court for what he had written.

Bertram dared him to act saying: “I am living still where my ancestors have lived for hundreds of years, and where I shall still remain till Christmas next, so that you know where to find me. I am not going to run away. I hold myself responsible for what I say, for what I print, as for what I do. Touch me, if you dare.”

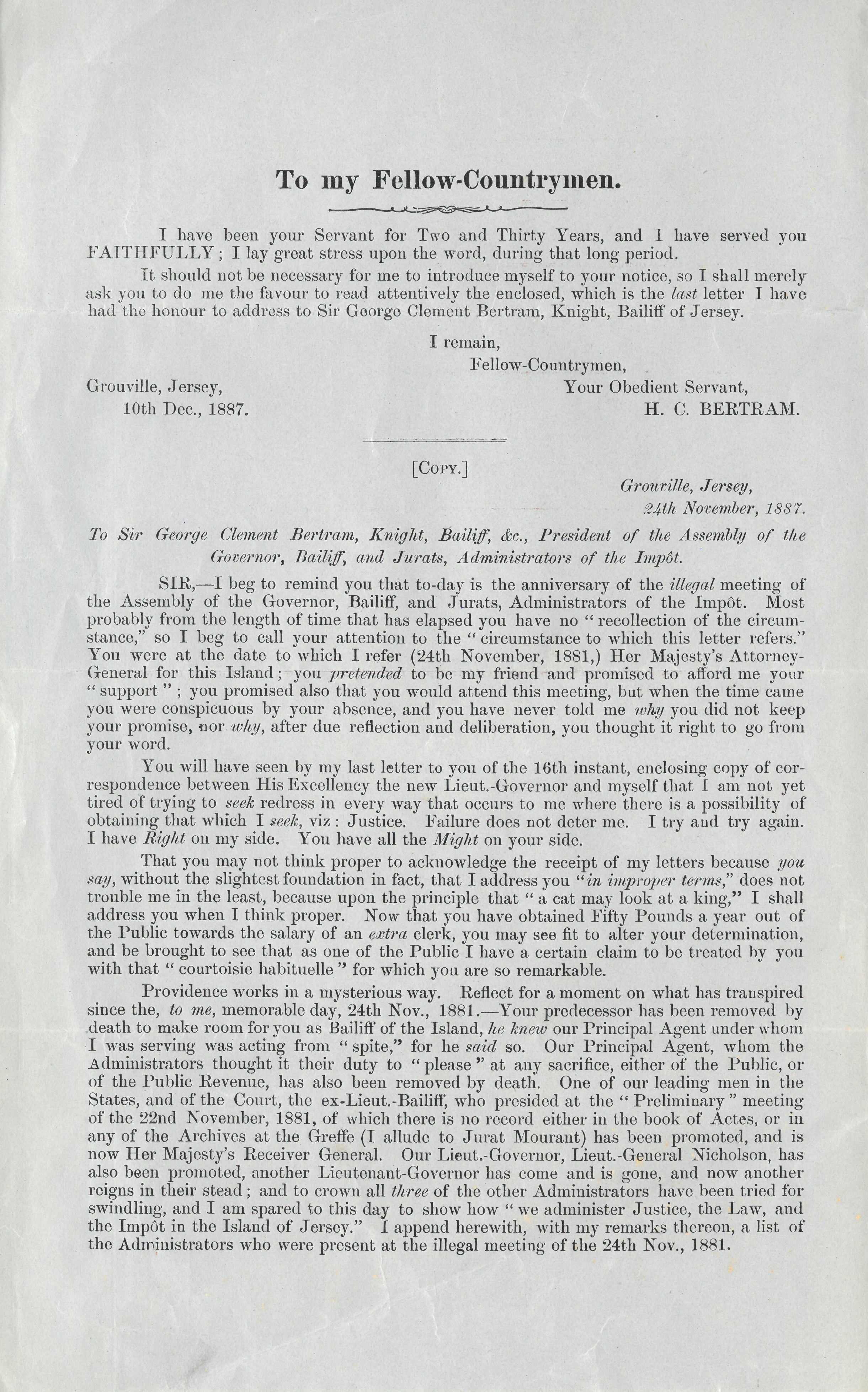

Pictured: Henry Charles Bertram's printed letter to the States Assembly in 1886 explaining his grievances. (Jersey Heritage)

In one of his letters he wrote: “You know that I am alive, and that while I am alive I shall be always kicking.”

These words proved to be prophetic as he fought to the last, dying on 1 October 1892, sadly without receiving the final justice that he was hoping for.

This piece, put together by the Jersey Archive team, tells just one of the many stories hidden in its collection.

To uncover more like this, visit Jersey Archive in Clarence Road or search the JEP Photographic Archive on its website HERE.

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.