A Second World War fighter pilot who would go on to personify the golden age of post-war commercial aviation in Jersey is celebrating his century today.

Captain Bernard Gardiner – who flew the Hawker Typhoon over Northern Europe, bombing railway lines supplying V1 and V2 launch sites, before becoming the founding pilot of Jersey Airlines – remains sharp-minded, active and passionate about aviation.

Only two years ago, he fulfilled a lifetime ambition to fly in a Spitfire, that much-cherished aircraft that had eluded him during his busy wartime service.

Bernard’s post-war career might not have had the bare-knuckle tension of bombing runs over Holland but it was no less significant: flying thousands of islanders and visitors to and from the island in an assortment of aircraft.

Through the tourist boom years of the 50s, 60s and 70s – of cabarets, cheap tobacco and honeymooners – Bernard bought the masses to and from Jersey on Herons, Heralds, Dakotas, Viscounts and other aircraft that were the workhorses of the skies at the time.

Pictured: Bernard as a young RAF recruit in 1940. He is on the far left of the very back row.

Express met Bernard at his home at the top of Market Hill in St. Aubin, which has wonderful views over the bay. He makes a point of walking down and up the rather steep hill every day.

Recounting where it all began, Bernard said he was born on 6 April 1922 in the wonderful named city of Moose Jaw, which is in Saskatchewan, Canada, where his father ran a cattle ranch.

The family returned to England when he was four and by the time war broke out 14 years later, he was working for a photographer in Gloucestershire.

“I had always wanted to fly,” he recalled. “[Aviation pioneer] Sir Alan Cobham had a Flying Circus which he used to take around the country. He had a vast variety of aircraft which he used to display and I won a ticket in a competition, which gave me my first flight.

“It was in an Airspeed Ferry biplane, which had an engine on each of the lower wings and another on top of the fuselage and held about 8 to 10 passengers. It took me on a circuit of the fields of Gloucestershire.”

With war breaking out in 1940, like all adult men, Bernard was conscripted into service.

“I was 18 and my date for getting called up was close. I could either join the army, air force, navy or go down the mines. I thought ‘I’m not going down there!’ so I went to the Royal Air Force recruitment office and signed up as a pilot.”

Pictured: Flying Officer Gardiner in Copenhagen in October 1945.

Joining up in October 1940, Bernard completed initial ground training at Cardington in Bedfordshire and then up in Blackpool. From there, it was out to Southern Rhodesia for flying training.

“We sailed in a big convoy from Liverpool, on to Glasgow and then out to the Mediterranean, at the time when the navy was busy chasing the Tirpitz around. That was a bit worrying for us because we were on deck most of the time, standing there with our life-jackets on, waiting to be torpedoed.”

Although he trained to fly on single-engine fighters, he may have had a different war had he not looped the loop one day.

“Because I had ideas of civil aviation after the war, I originally chose to go to a twin-engine school although initial training was in a Tiger Moth,” he said.

“The instructor took me up to do some aerobatics. What he didn’t know is that I’d been practising aerobatics when I should have been rehearsing forced landings. He said, ‘We’re going to do a loop together’, so he flew a loop and I followed the controls.

“He then said, ‘Ok, you do one’, and I did a perfect loop, which is when you hit the slipstream you make on the way up. He said, ‘Do that again’, which I did, hitting the slipstream again, and he said, 'Right, you’re for fighters!'

“And that was me out of the twin stream into single-engine flying from then on.”

Pictured: On the promenade in Dinard in 1952.

Bernard flew the Tiger Moth and the North American Harvard in Africa and then came back to England to serve in various squadrons, “really, just wasting time”.

It was then on to operational training in Hurricanes and Typhoons. He recalls that in those early years of the war, the Typhoon was beset by engine problems and also had a rather bad habit of losing its tail.

“So, I got through that training and then did fill-in jobs in various squadrons,” he recounted. “Then, in October 1944, I was called out to the continent and that’s when my combat flying began, flying the Typhoon in operations against the Germans.”

Bernard joined 193 Sqn, whose primary role was ground-attack operations, mostly trying to prevent the enemy moving V1 and V2 flying bombs to their launch sites by breaking the railway lines that transported them and their supplies to the Dutch coast.

“Unfortunately, the Germans were very good at immediately rounding up any working person, big or small, to repair the railway lines, so they were repaired almost before we had landed back at base, but we kept at it.

“Initially, I joined the squadron in Lille, and then we moved up to Antwerp and most of my operational flying was from that city.

“Once liberated, Antwerp became the major port for importing all the materials for the British, Canadian and American armies so the Germans were quite keen on putting it out of use as a port so we were on the receiving end of lots of V1s and V2s as well.”

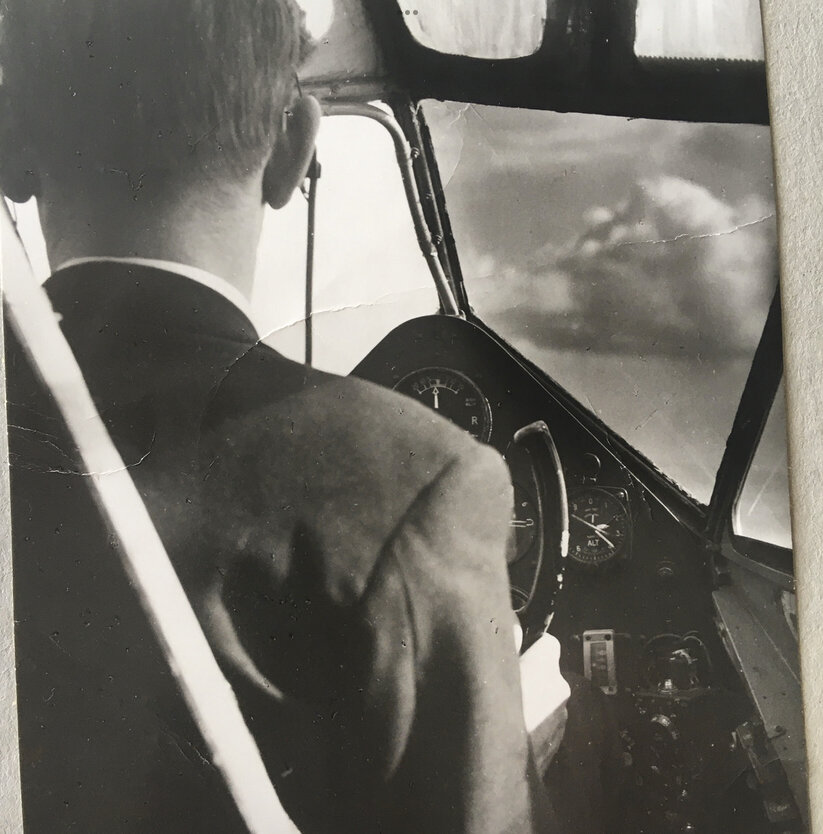

Pictured: Bernard at the controls of a de Havilland Rapide, which had a single pilot, in October 1952.

Recounting his missions, he said: “Despite its earlier difficulties, the Typhoon was a lovely plane to fly, with immense power – it had over 2,000 horsepower and a great big 14-ft-diameter propellor.

“We could stay up for about 45 minutes, and we were usually pretty close to the bomb line. So, we would do a quick sortie across the bomb line to attack the Germans, and then we’d come back again.

“The army, to some extent, were able to call on us when they needed us. We were given a briefing on what to attack and then we’d be up, armed with rockets or bombs.”

Fortunately by that stage, the Luftwaffe had been virtually neutralised so Bernard did not face the aerial battles that were synonymous with the earlier years of the war.

“The first and only time I came across airborne German aircraft was on the last operation of the war on 3 May 1945, and that was a flying boat taking off rather foolishly underneath us.

“It didn’t last very long.”

Pictured: Posing on the airfield in Alderney after landing a four-engined Handley Page Dart Herald in October 1956.

His only encounter with enemy fire was when an anti-aircraft shell burst fairly close to him and a splinter took out his radio-set.

"I had a lucky war," he said.

Bernard flew 71 combat missions over German-occupied Europe. Completing 72 would have meant a training post back in England but the war thankfully came to a close.

He stayed in Germany for 18 months after VE Day, based south-west of Bremen.

“We were still flying Typhoons and could take the aircraft up and enjoy ourselves. The top brass wanted us to impress the Russians so we would form up in very large formations.”

As hot war turned to cold, Bernard left the RAF and pursued his dream of becoming a commercial aviator.

“Just before I left, I went to see an RAF officer, whose role was to sort out what sort of job we could go to in civilian life. I didn’t particularly want to go back to photography, so they gave me a grant to go to London to get a navigator’s licence.

“I asked ‘why a navigator’s licence, when I’m a pilot?’ but that was the stepping stone to a commercial pilot’s licence then. I went off to London and studied for three months and got a second-class navigator’s licence, as well as a commercial pilot ‘B-licence’.”

Bernard’s first job was up in Prestwick as a junior co-pilot, flying Dakotas with Scottish Airlines.

“We were operating British European services for them because all they had at the time were Junker 52s, which had been requisitioned from the Germans. The Dakotas were, unsurprisingly, much preferred by passengers."

Pictured: Capt Gardiner frequently flew ‘Romeo Golf’ - the Jersey Airlines Heron that sits on the apron at the Airport.

He continued: “I stayed with Scottish Airlines for a while but when BEA themselves got Dakotas, I was made redundant. So I went back home to Gloucestershire, where I saw an advert from someone who wanted a pilot to fly day trips from Jersey to Dinard.

“I went up to London, and they asked if I could leave right away for a fortnight in Jersey but I didn’t have anything with me, so I left the next day, flying from Croydon to the island.”

This was 1949 and Bernard became the first pilot of the fledging Jersey Airlines, which was being formed by businessman Maldwyn Thomas.

“We sourced re-equipped Rapides and gradually acquired more and more pilots. Eventually, we grew large enough to get Dakotas, Herons and Heralds.

“We also became associated with British United, which was based at Gatwick, so we got Viscounts as well.”

Pictured: Capt Alan Spencer shakes the hand of Her Majesty, with Capt Gardiner alongside him, at the official opening of Gatwick Airport in 1958.

On 9 June 1958, Bernard was part of a Guard of Honour meeting the Queen when she officially opened Gatwick.

He flew a Heron on the first scheduled service into the new airport, and he and Capt Alan Spencer represented Jersey Airlines in the line meeting Her Majesty.

The British aviation industry in the 50s and 60s was typified by various amalgamations, which meant Bernard eventually ended up as chief pilot, operations manager and a director of British United Island Airways or BUIA.

Pictured: Capt Gardiner flew to and from Jersey in the 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s and 80s.

He stayed in the cockpit, however, all the way to his retirement in 1982.

“I never lost my love of flying all the way through, right up to my very last flight.

"It was the joy of being in the air and the freedom as much as anything else. That never leaves you.”

Watch: A long-held dream to fly in a Spitfire was finally realised in 2020. (Hawker Typhoon RB396/YouTube)

Retirement has largely been spent enjoying the company of his family.

He married the late Jean in 1944 and the couple had one son, John, who was born in Scotland in 1948 but moved down to Jersey the year after.

John has two sons, Matt and Kim, who are both based in the island.

Pictured: Bernard at his home at the top of Market Hill in St. Aubin, which he makes a point of walking down and up every day.

Bernard’s surviving brother, Peter, who is only in his nineties, lives in Devon and was also was a commercial pilot with BEA.

Bernard's family is keeping his 100th celebrations a surprise but he is aware that it involves a trip to the UK later this month.

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.