A Jersey mum is urging the Government to create dedicated services for children with eating disorders, after her daughter was sent off-island, away from her family, for treatment in the middle of the pandemic.

Sarah* described the “soul destroying” experience her daughter went through in having to be sent away, and the interventions she feels need to be added to Jersey’s services to prevent this happening to others.

She spoke to Express as new figures reveal a growing eating disorders crisis among young people.

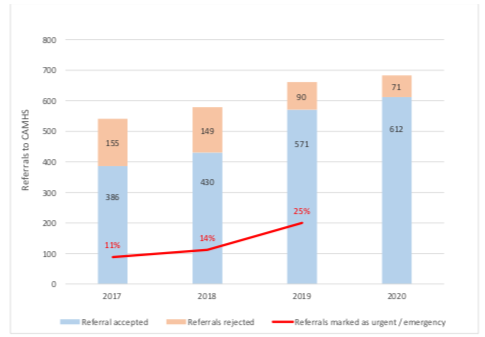

Pictured: CAMHS referrals have seen a year-on-year increase over the past four years.

In a recent report documenting the current strain on children’s mental health services, the Government acknowledged that the “number of children with eating disorders is growing but we do not yet a dedicated service for them.”

The report showed that eating disorders in young people had more than tripled in the past four years, with 44 cases currently recorded on-island as of April 2021.

In a bid to raise awareness of the seriousness of eating disorders' effects on children, Sarah has spoken in-depth about her daughter's experience, and what she believes the Government needs to do to improve the help available.

Pictured: Lockdown led to a lack of control, something that has been noted as a key pattern in triggering eating disorders.

Before the illness took hold, Sarah described her daughter, Lucy*, as a “happy”, “independent” and “high-achieving” young person.

However, during lockdown, her everyday life changed. With no school, no access to extra-curricular sporting activities, and extended periods of time at home, Sarah explained that her daughter “had no control anymore", and began obsessing over eating healthily and exercising - a pattern of behaviour the Chair of Jersey Eating Disorders Support previously told Express was well known to them.

Along with noticing it herself, it was a shocked family member's remark - "how much weight has she lost?" - that reinforced the need to seek medical help.

After doing several tests, the pediatrician concluded that Lucy's Body Mass Index was fine, and that as they only worked medically rather than in mental health, they could do no more than recommend eating more, referring her on to CAMHS.

“In her mind, that meant she was nothing wrong with her, and she spiralled,” Sarah said.

Pictured: As the paediatrician could not intervene from a mental health perspective, all they could advise was to eat more, and refer Lucy to CAMHS.

Even when she saw CAMHS a few weeks later, Lucy's mental and physical health still continued to deteriorate despite the sessions. She was losing more and more weight at a rapid pace.

Sarah said she felt they were focusing on other issues rather than tackling the disorder directly.

“I don’t know what was happening in those sessions at CAMHS, but clearly it wasn’t helping… she started restricting even more, she started exercising even more.”

The situation then continued spiral, with Lucy then being admitted to Robin Ward as a CAMHS patient.

The immediate situation was so serious that when Sarah brought her Lucy to Robin Ward, there were what she described as “horrific” scenes of doctors trying to recover her. She described the situation as like “something out of Holby City… her whole body was shutting down.”

Sarah was later told that, had Lucy come to hospital only a couple of hours later, she would have been in Intensive Care.

She was put on a drip and began to make a physical recovery. Mentally, however, it was a different story.

“They got her medically stable but her mental health deteriorated rapidly… it was like I left one night and came back the next day to a completely different child.”

Lucy was kept in the CAHMS cubicle of Robin Ward, where she remained for several months.

The facility was not a comforting, homely environment appropriate for a child, Sarah recalled, but more clinical, more akin to a generic mental health ward bed.

There, Lucy had to be fed a supplement called Fortsip through a nasal-gastric tube to give her calories. The process was not always an easy one, and could sometimes involve restraint by nurses.

Pictured: Lucy was admitted to Robin Ward after her illness rapidly spiralled and she lost a dangerous amount of weight.

Two healthcare assistant were put on constant supervision duties to ensure the safety of Lucy – who would sometimes self-harm or attempt to remove her tube.

Sessions with CAMHS individuals would mostly only take place on a weekly basis – falling short of the intensive therapy Sarah felt something as serious as an eating disorder would require.

Sarah recalled how many multi-disciplinary meetings about Lucy’s welfare simply resulted in her medication being increased, rather than more therapeutic interventions.

“These kids are stuck in a bed, and all they’re getting is their food put in front of them every two hours and that’s it - they’re not getting the art therapy or someone coming in and doing your nails and trying to boost your confidence like you get in an inpatient unit.”

Giving an example of this lack of understanding, she explained how a dietician employed to suggest foods for Lucy to eat orally would often include items that she had already expressed a clear dislike for - foods that would put her off eating.

“It got to the point where the meal plan was coming out, and I was sat with the nurses saying, ‘No, send it back, get it changed.’"

She explained that for someone with an eating disorder, one bad experience with food can throw a whole day off track: “If she wakes up and says she wants to eat her breakfast [and is given something she doesn’t like]... that ruins the mindset of that whole day.”

Pictured: Sarah expressed her frustration that the dietician appointed by health was putting food Lucy didn't like on the diet plan nurses had to serve her, even when she had been told of the adverse effect they would have.

Though she was critical of the training given out by Health, and lack of therapeutic provisions to deal with those with serious eating disorders, she made clear that the Robin Ward staff and “nurses are phenomenally amazing”, saying she could not fault “absolutely everyone within that ward - I would never, ever have survived it without them.”

Furthermore, she observed that these nurses are currently being inundated with an increasing number of serious mental health cases.

On three occasions last year, it was even necessary to accommodate CAMHS inpatients on the adult ward of the hospital.

“They are there to deal with sick children, not mentally ill children – but there’s nowhere else for these kids go, so they go to Robin Ward,” Sarah remarked.

After a number of months at Robin Ward, it was decided that Lucy would have to be sent off-island for specialist treatment, as Sarah explained that “Jersey just didn’t know what to do.”

After a six-week wait for a bed at a treatment centre, Lucy departed the island to go to the centre.

Pictured: Lucy was eventually sent off-island, after it was decided Jersey was not able to treat a case as serious as hers.

Sarah recalled the difficulty of having to say goodbye to her daughter "in the middle of a pandemic".

Lucy, meanwhile, had very little information about what to expect - "she hadn’t met staff, and we didn’t have a clue other than what we could Google.”

The premises was shared with children with even more severe difficulties - Lucy's mum said some of the sights she saw “absolutely destroyed her.”

Lucy also told her mum that she wasn't always given the choice to physically eat food at mealtimes at the off-island facility, sometimes only being offered a tube.

Pictured: Sarah said that Lucy saw things that "absolutely destroyed her" whilst at the off-island facility.

However, she did praise the facility's communication. In weekly video meetings between herself, the facility and CAMHS, the off-island unit managed to get nearly all of their staffing team to give updates on Lucy’s progress every time.

After several months, Lucy eventually left the facility after making improvements - though Sarah believes this to have been down to Lucy herself rather than the treatment she received "because she just wanted to get out of there and get home."

Upon returning to the island with Lucy from the centre, another crisis hit - when the family had to isolate for 10 days, they say they received next to no input from Jersey’s mental health services.

This, Sarah said, had a "massive impact" that led Lucy to spiral and attempted to take her own life.

Sarah said regular interventions only seemed to pick up after this point.

Pictured: With a lack of intervention during the isolation period, an ambulance had to be called twice during the family's return to the island.

CAMHS engagement has now increased, with a number of sessions each week involving different staff.

However, with Lucy living at home, Sarah must now look after her daughter 24/7 to ensure her wellbeing, with no respite.

She highlighted that there was little “out of hours support” and that “at the weekends when it tends to be the worst, there’s no one to ring and get support from.”

She is also concerned that she does not have the specific training or capability to intervene and stop certain behaviours.

Despite these challenges, Sarah said she felt the family had "turned a corner" and that, mostly due to Lucy's "determination to get better", she was now in a "much better place".

On this note, she encouraged parents and children similarly affected to know that “they’re not alone – it is traumatic, it is horrible but there is light at the end of the tunnel, if you just keep pushing; it’s difficult but we get there.”

Following the trauma of the past year, Sarah is now calling on Jersey’s Government to do more for children with eating disorders.

She wants to see early and immediate preventative measures put in place to ensure children get help before its too late, rather than remaining on a waiting list.

Most crucially, she wants to ensure that children with more severe illness can receive dedicated therapeutic care in Jersey, rather than being sent away.

Pictured: Sarah said that she did not blame CAMHS staff, who she thought were trying their best, but wanted more resources for them, and more specialist eating disorder training.

“Why does a Jersey-born child have to be sent away? In the pandemic, in the middle of a mental health crisis, why is there no support for our children? All this money that was spent on sending her away – couldn’t it have been spent on-island?”, she asked.

“Sending them away from everything they know is cruel, it’s horrible - how are they meant to get better?”

She suggested the creation of a dedicated therapeutic centre, and increased training for both CAMHS and nursing staff to better understand eating disorders and serious acute mental health issues, as well as early prevention safeguarding put in place to intervene as soon as possible.

Sarah emphasised that the problems did not lie with CAMHS staff, but the "system" they worked in.

“You can’t blame the individuals in CAMHS, it’s not their fault - they are just so under-resourced,” she said.

She said she wants to see more training and understanding of conditions like her daughter’s, as well as more funding for specialist services.

Pictured: Sarah said that she wanted to see the money spent on sending a child off-island, put into setting up a dedicated on-island facility to treat eating disorders and similar severe mental illnesses instead.

This strain on resources is reflected in both the increase in caseload of over 50%, and the increased backlog in the recent past.

This month’s mental health strategy report also notes that “the Jersey CAMHS team is small when compared with other islands,” with the Isle of Man having more staff on their service despite the island being a quarter smaller than Jersey."

As a model for how a refreshed, therapeutic service for eating disorder sufferers could look, Sarah highlighted Silkworth’s recent Hope House development.

“Why can Health not provide something like that - not only for eating disorders, but for all the other children out there who are suffering from social anxiety or just general mental health conditions?

"To have somewhere like that to go to would make such a difference to children’s lives.”

Express has contacted the Government for comment.

*Names changed to protect anonymity.

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.