At a towering 1,000 pages, the Care Inquiry report is a formidable read: a “harrowing” catalogue of child abuse and authority failings spanning more than half a century in Jersey.

Here, Express digests the facts, figures and key findings of the report.

3 years: from 2014 to 2016, the Inquiry sat for 149 days of hearings and consultations.

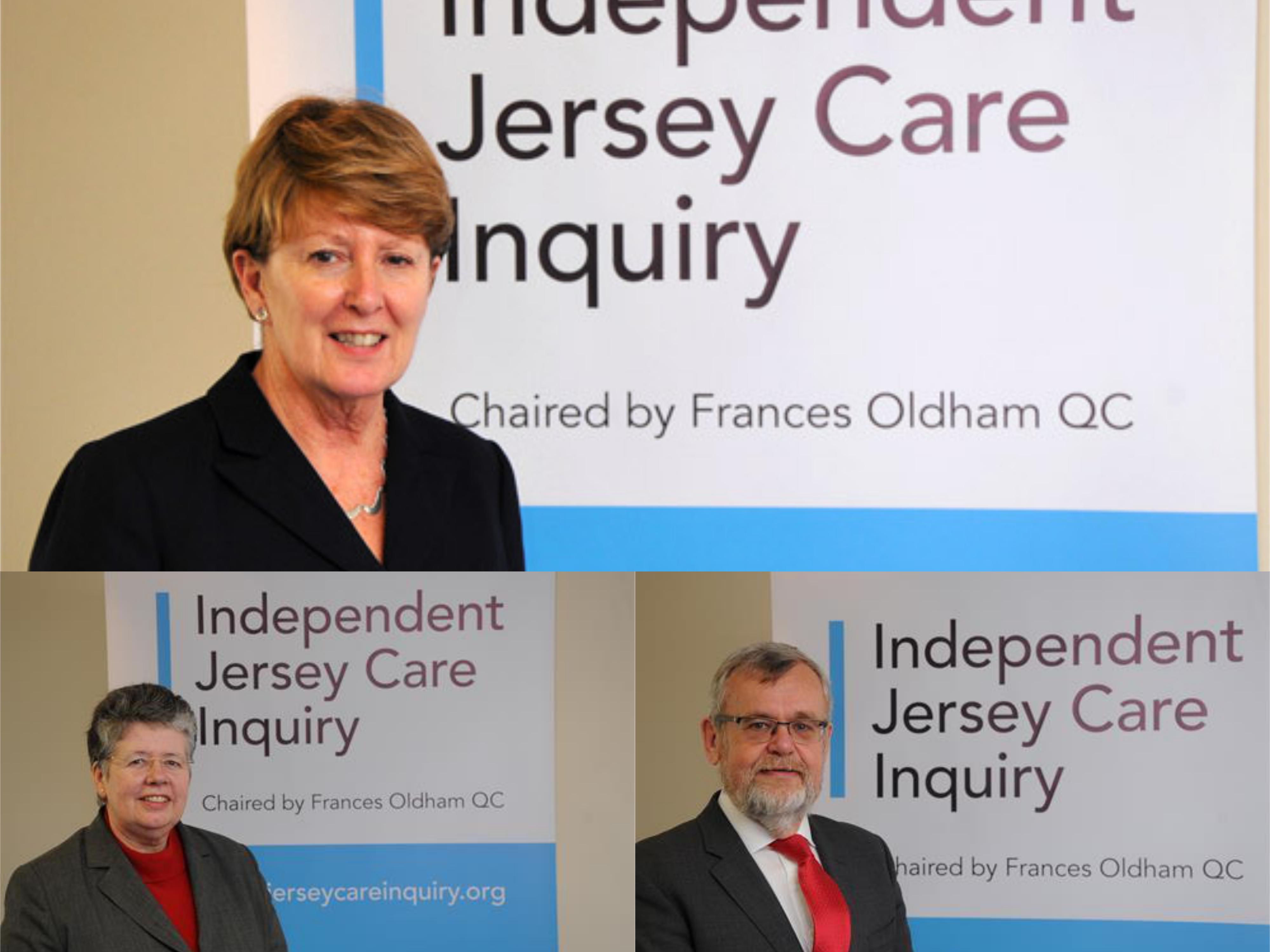

3 independent panel members presided over evidence from Frances Oldham QC (Chair, pictured), Alyson Leslie and Professor Sandy Cameron CBE.

Pictured: The three members of the Independent Jersey Care Inquiry Panel.

Over 136,000 documents

Over 450 previous residents of Jersey’s care system and over 200 witnesses.

Over £20 million (potentially £23million) worth of government funding – around £14 million of which was lawyers fees alone.

Children ended up in care for petty reasons – including for offenses as minor as “rude and cheeky” behaviour.

When struggling families asked for help from the Parish, Constables could get children placed into care – without any statutory order.

Once children were in the care system, it was extremely difficult for them to leave, with little to no support in place for them to be re-integrated with their families or society.

Pictured: Children were "abandoned" in draconian and authoritative care systems with little prospect of ever leaving, the report found.

The children who were “abandoned” in the system were subjected to intense physical, emotional and sexual abuse – at the hands of carers, neighbours and even other children.

Young offenders were housed in the same accommodation as other children, but both were treated the same.

Such treatment left the children likely to succumb to “exploitation, addiction, crime and depression” later in life.

Children "may still be at risk" now, given poor measures currently in place to protect them.

For a long time, there wasn’t an official way for children to report concerns – and the processes later brought into place were seen as “daunting”.

Even when they did speak up, children were regarded by numerous institutions as “liars”, particularly young offenders who were branded “little villains” by authorities supposed to protect them.

Pictured: Among other failings, for a long time there was no formal system for children to share their fears and concerns with others - many of the homes were deeply "unemotional" in their treatment.

Up until 1997, the law wouldn’t take them at their word and said that any allegations of abuse needed to be backed up before they could be taken seriously.

External inspections of the institutions were few and far between – one ran for 70 years without review. Even in the mid-noughties, independent inspections were few and far between.

"The Jersey Way’ – a focus on protecting the Island’s reputation at all costs – and a keenness to prioritise finance over social issues saw many cases overlooked.

"These failings impacted upon children who were already at a disadvantaged whether through family circumstances, a crime committed against the child or even a crime committed by the child," Frances Oldham QC observed.

Staff members were often poorly trained - or not trained at all – and didn’t know how to cope with such isses, with some having got their jobs through “local connections” rather than based on skills.

The report makes eight key recommendations to protect children in future:

Create an independent Commissioner for Children role.

Build an adequate complaints system, which should be the subject of an annual report.

Pictured: One of the recommendations was to tear down Haut de la Garenne, a symbol of "trauma" and "shameful history" for many of the victims.

Conduct regular inspections of services.

Ensure that staff are adequately and sustainably trained.

Draft appropriate legislation to protect children.

Make States members swear to look after children as part of their Oath of Office.

Pictured: The Jersey government should be encouraged to put children's rights before finance and reputation, the report advised.

Address the “fear factor” and “lack of trust” stemming from ‘The Jersey Way’ - a culture of putting its reputation as an international finance centre above investigation.

Provide “tangible” public acknowledgement of victims and ensuring that reminders of the years of abuse are destroyed – including the Haut de la Garenne building.

"I am shocked. I am saddened. I am sorry."

"I accept, every recommendation and pledge to build a new culture. One which puts children first. Every time. Where one child failed, is one too many."

Video: Chief Minister apologises to victims of abuse in the Island's care system.

"People have been let down and I am sorry for that. Children should never have been abused. They should not have been failed, but they were."

"Now our priority is to take action to help ensure that no child suffers such abuse in future."

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.