After years of concerns over a rising population, could depopulation actually be Jersey's next major problem? New figures have shown that more people left the island than arrived between 2019 and 2021 – with most leavers long-term residents and 'Jersey Beans'...

It comes little more than a week after a new Government report said that Jersey may require a population of 150,000 people by 2040 in order to maintain the living standards that all islanders enjoy.

Express took a closer look at the new stats, why people might be leaving, and one Minister's suggested solution to the 'brain drain'...

Over those three years, an average of 180 left Jersey over and above those arriving.

The figures were released by Statistics Jersey after the unit updated the way it analyses relevant data, such as tax payments and employer manpower returns.

Although the population naturally grew by 120 in 2021 because of more births than deaths, net outward migration was 310.

Breaking the net migration figures for 2021 down, 910 islanders who had ‘Entitled’ or ‘Entitled for Work’ status left the island.

These outward migrants included residents who came to the island with ‘Registered’ status five to nine years previously, so it was not just long-term residents leaving Jersey for pastures new.

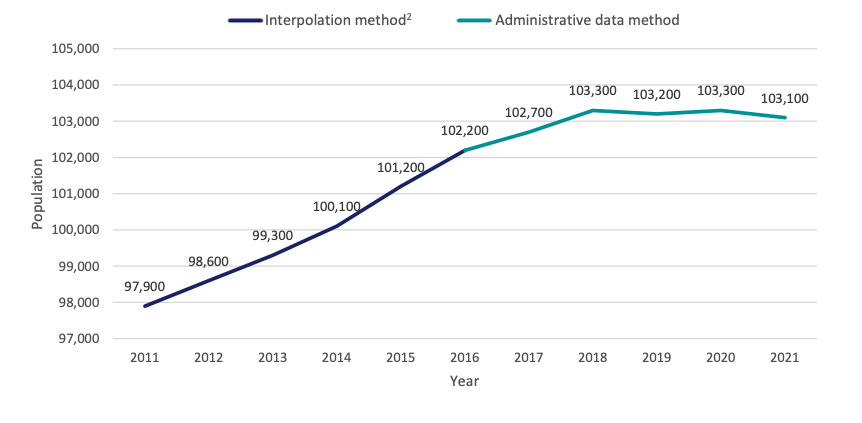

Pictured: The island's population since 2021, with the two colours representing a different method of data collection by Statistics Jersey.

Also leaving the Island in 2021 were 20 more children than those arriving, and 80 more over-64s than the same age group settling in the island.

Conversely, 520 more ‘Registered’ people came to Jersey that year than left, and 180 more ‘Licensed’ people came than departed.

In short, people who had lived in Jersey for at least five years, and possibly their whole lives, were the largest group leaving, while those considered an 'essential employee' or an 'unqualified' worker formed the largest group arriving.

The new statistics show that Jersey’s population has plateaued since 2018 and dipped slightly in 2021 to 103,100.

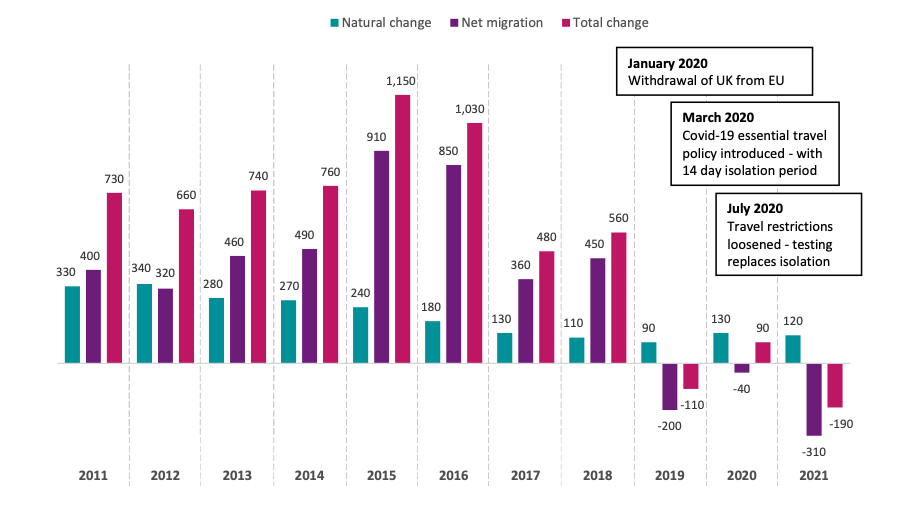

Pictured: Natural change, net migration, and total change in population size by year between 2011 and 2021.

However, overall, the number of Jersey residents has been climbing over the past 10 years – on average, by 770 people a year between 2011 to 2018, followed by very little change between 2018 and 2021.

Over the decade, the population increased by 520 people each year on average.

Over the same period, the difference between births and deaths narrowed considerably. While births continued to exceed deaths, in 2011 there were 330 more births than deaths, yet this had fallen to 130 by 2017. It remained between 90 to 130 for the rest of the period.

The new analysis by Statistics Jersey gives a clearer picture of the island’s population between 2017 and 2021.

It shows that the inward and outward migration flows were, on average, around 4,000 people moving in each direction each year between 2017 and 2021.

More working age people with ‘Entitled’ or ‘Entitled for Work’ status left Jersey than the number that entered in every year between 2017 and 2021, with an average net outward migration of 580 people per year.

Someone is ‘Entitled’ if they have lived in Jersey for at least 10 years, while an islander ‘Entitled to Work’ has been resident for at least five. ‘Licensed’ means essentially employed while ‘Registered’ is, in effect, ‘none of the above’.

Statistics Jersey's new report doesn't examine the reasons for departure – but it is notable that the population decrease occurred during a three-year period which included the UK leaving the EU and the covid pandemic.

During the early stages of the pandemic and associated lockdowns, many of the island's migrant worker population returned to their home countries.

Brexit and the subsequent end of free movement, as well as reduced connectivity, created complications in bringing them back as the island began to reopen, which the hospitality industry in particular bemoaned on several occasions, calling it the "perfect storm".

High rents, unaffordable house purchase prices and the escalating cost-of-living have also likely played a part in the decline. Living costs rose by 12.7% between March 2022 and 2023.

The owner of local removals business Good Moves, Mike Philips, told Express last May that the flow of islanders leaving Jersey “just hasn’t stopped since the initial lockdown in 2020" – and that such moves were happening across the spectrum of wealth.

Pictured: "It just makes more financial sense to relocate to the UK where people can get more for their money," Good Moves' owner said.

Musician and islander of many years Dina Andrews, who performs as 'The Pink Cowgirl', bade a poetic farewell to the island last year as a direct result of basic living costs.

Meanwhile, owners and founders of the Jersey Seaweed Co organic fertiliser business, Francesca Stammers and Loftur Loftsson revealed to Express in May that they were looking for someone to continue their business after cost of living challenges saw them decide to swap Jersey for Mallorca – where they're hoping to start an organic farming venture.

High costs also appear to have contributed to a reluctance to move to the island.

Pictured: Dina Andrews said the last straw for her came one day when she ended up forking out £7 in a Jersey shop for the "bare essentials" – "a few tins of beans and a carton of milk".

The Jersey Appointments Commission – which oversees public sector recruitment – said in its annual report published last month that Jersey's cost of living, including housing and childcare costs, was causing "significant challenges" in recruiting overseas job candidates.

Jersey's population is ageing as those who moved to the island in the 60s, 70s and 80s reach retirement age.

In 1961, Jersey's population stood at 59,489 but this had grown to 97,857 by 2011 – a 64% increase.

The Government recently released its Common Population Policy, which predicted that the island would need 150,000 people by 2040 under current economic circumstances – largely due to the ageing population. Chief Minister Kristina Moore said this figure was not acceptable, however.

To fund this growing group of pensioners, the Government says that the working population needs to become more productive through, among other things, the adoption of technology and developing new industries.

Deputy Chief Minister Kirsten Morel, who leads the Economy Department, recently proposed a somewhat controversial solution to the 'brain drain' of young people – converting grants given to university students to loans if they do not return to the island.

Deputy Morel said that he would like to create incentives for Jersey students to come back once at some point once they have completed their studies.

Stressing that he was speaking a personal capacity, he said: “At the moment, half the people we fund do not come back to Jersey.

“That mean we are effectively funding other jurisdictions’ economies, and we should be doing more to stop this brain drain. To put it in pure economic terms, the island is not getting enough return on our investment.

“It is personal view, but I am talking to other ministers about it. I cannot speak for them, but I think there is an acknowledgment among other ministers that there is a brain drain and we need to explore mechanisms to stem that.”

The Government provides financial help for students who are resident in Jersey and who wish to undertake a course in higher education or postgraduate professional education.

Pictured: Deputy Kirsten Morel: "I think it is something worth discussing at the Council of Ministers"

A means-tested grant may be payable and is composed tuition fees of up to £9,250 per year, and a maintenance grant of up to £8,572 per academic year

To achieve this top £17,822 level, a student’s total ‘relevant income’, which may include the income of their parents and / or spouse, must be less than £60,000.

Responding to Deputy Morel’s comments, which he gave in response to a question after delivering a speech to the Chamber of Commerce this week, Nicki Heath of the Student Loan Support Group said that care needed to be taken when discussing "return on investment".

FOCUS: Can Jersey avoid hitting 150,000 people by 2040?

Comments

Comments on this story express the views of the commentator only, not Bailiwick Publishing. We are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any of those comments.